[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Let’s start off with a truism. And that truism, quite simply, is that within the HUD manufactured housing program, the so-called “monitoring” function has grown, expanded and metamorphosized over time, to become something that it was never meant, designed or intended to be, with a private contractor exercising defactogovernmental authority over regulated parties. Of course, HUD claims (and protests loudly whenever confronted) that ithas the final say, and the final authority on all regulatory matters, and that, as a result, everything is perfectly legitimate. But the reality, for decades – in fact, since the very inceptionof the HUD program more than forty years ago – has been quite different.

A detailed review and analysis of the last monitoring contract by MHARR (see, MHARR Viewpoint, October 2015, “Monitoring Contractor’s Domination of Federal Program Must End”), shows quite clearly that the program monitoring contractor is (and has been) tasked by HUD with the performance of pseudo-governmental functions, and rendering what amount to final decisions on discretionary enforcement matters, often with no substantive involvement by responsible HUD officials at all. And driving the inexorable expansion of contractor functions over time, the inexorable expansion of related regulatory burdens and costs imposed on regulated parties, and, not surprisingly, corresponding increases in monitoring contractor revenues — has been a defacto, HUD-sustained monopoly on the program monitoring contract by just one entity (the Institute for Building Safety and Technology, “IBTS,” previously named the National Conference of States on Building Codes and Standards, “NCSBCS” and Housing and Building Technology, “HBT”).

For any of the Trump Administration’s regulatory reform agenda to have a real or lasting impact on the federal manufactured housing program, however, the Administration’s political leadership at HUD mustassert itself, the 40-year-plus monitoring contract monopoly mustbe ended, and the contracting process itself mustbe reformed in order to produce full and fair competition, as required by law throughout the federal government. Sadly, though, after a seemingly promising start, concern is growing that this particular aspect of “draining the swamp” could be starting to backslide in the wrong direction – unless, that is, the entireindustry and consumers take action to stop the slide.

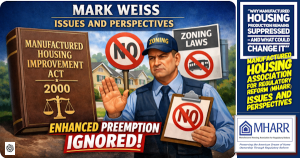

Why is the monitoring contract so important? Well, the Trump Administration and Secretary Carson have taken a number of important steps to startthe process of reforming the federal program, and to bring it back to what Congress and the law – particularly the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 – designed it to be, a preemptive program of minimum performance-based standards and uniform enforcement that protects consumers while simultaneously preserving, protecting and advancing the inherent (i.e., non-subsidized) affordability of manufactured homes. At MHARR’s specific urging, the Trump Administration, in late 2017, replaced and re-assigned the over-reaching career administrator of the HUD program, Pamela Danner. Shortly thereafter, again as advanced by MHARR, HUD began a “top-to-bottom” review of all existing (and proposed) HUD standards, regulations, and pseudo-regulatory action (such as “Interpretive Bulletins” and “Field Guidance” documents), incident to concurrent rulings by the Attorney General that the Justice Department would not undertake enforcement actions in federal court based on such “pseudo-regulatory” guidance documents.

Both of these actions represented necessary first-stepsto begin the process of restoring the rule of law – and common-sense – to the federal program, consistent with the express statutory purposes of the 2000 reform law. The job, though, does not end with initiating a “process.” “Process,” in and of itself, is not a goal. Positive, substantivechange within the program and for both the industry and its consumers is the goal. For genuine progress, the program administrator’s position, for example, must now be filled by a non-career appointee, as required by the 2000 reform law, andthe regulatory reform process initiated under Trump Administration Executive Orders 13771 and 13777 must lead to substantive action by the Administration to repeal (or significantly modify) layer-upon-layer of unnecessary and debilitating regulations, interpretations, and pseudo-regulations, developed and imposed over time with little or – in most cases – noconsideration for their impact on the cost of manufactured housing or the ability of lower and moderate-income American families to purchase a manufactured home.

As important as those steps are, though – and ultimately could be with proper follow-through – real, on the ground, and lastingchange for the federal program will require a fundamental shift in the way that the program does business with respect to the monitoring function, including the monitoring contract itself, the nature and scope of the monitoring function, and ultimately, hiring a new program monitoring contractor after 40-plus years of defactomonopoly.

Thatdefactomonopoly, for which MHARR has been unable to find anyparallel anywhere else in the federal government, is the most compelling and probative evidence that the HUD monitoring contract process itself is entirely dysfunctional. While repeated monitoring contract procurements at HUD, since the inception of the federal manufactured housing program, have allegedlybeen “competitive” in nature (as defined by federal law), and have been conducted asallegedlycompetitive procurements (i.e., without the formal protections required by law for non-competitive, sole-source contract solicitations), the facts show this to be patently false (and arguably fraudulent). Instead, based on HUD contract “award criteria” that, through successive solicitations, have been tailored to match the “experience” of the one and only entity to ever hold the contract – i.e., NCSBCS/HBT/IBTS – the monitoring contract procurement, through its entire history, has been a defactosole-source procurement without any type of meaningful, actual or legitimate competition.

Indeed, on the one occasion when a competing bid, lower than that of the one-and-only monitoring contractor –IBTS — wassubmitted, nearly three decades ago, by a highly-respected and credible code organization (i.e., the former Council of American Building Officials – “CABO” — now, the International Code Council – “ICC”), HUD, rather than awarding the contract to another entity, initiated a “best and final” round of revised offers, which ultimately led to an award, once again, to the one-and-only monitoring contractor — IBTS — (as shown by documents grudgingly provided by HUD to Congress after multiple requests by former North Carolina Senator Lauch Faircloth).

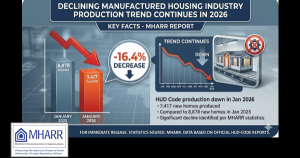

This contract manipulation and the resulting domination of the program over the course of its existence by oneentrenched, self-servingcontractor, has had a ruinous effect on the HUD manufactured housing program, the industry itself and consumers in particular, as the purchase price of manufactured homes has needlessly been inflated by unnecessary, unjustified and baseless expansions of regulatory compliance burdens at the initiative and behest of the entrenched monitoring contractor. Indeed, detailed MHARR analyses have demonstrated how HUD payments to the monitoring contractor have ballooned over the past decade in particular (to more than $25 million in the last five-year contract), even as industry production levels have fallen to historic lows and referrals to the HUD dispute resolution system (reflecting unresolved consumer issues in new HUD Code homes) have been – and remain – at microscopic levels, well below 1% of corresponding industry production over the same period.

The needless regulatory costs and burdens imposed because of the contractor, moreover, disproportionatelyimpact and harm smaller industry businesses (and consumers of affordable housing) while conversely benefitting the industry’s largest producers, which can spread spurious pseudo-regulatory costs over a larger base of production. It should thus be no surprise that you will hear little or nothing about this issue from other industry organizations, which are beholden to the support of those larger entities.

Recognizing this as a major structural and policy problem within the federal program — as a result of education efforts by MHARR — Congress, in the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000, attempted to halt this manipulation of the HUD contracting process. Remedial provisions thus inserted in the 2000 reform law by Congress included, among other things, a mandate for an appointed, non-career program administrator, a requirement for “separate and independent” contractors for monitoring and other functions, a narrow and limited definition of the “monitoring” function (i.e., the “periodic review of the primary inspection agencies … for the purpose of ensuring that [they] are discharging their duties under” the 1974 Act as amended), and a requirement – in section 604(b)(6) – for notice and comment rulemaking and Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee (MHCC) review and approval for all changes to HUD policies, practices and procedures concerning enforcement-related activities.

HUD, though, over the past two decades, has either totally ignored, unduly restricted, or chipped awayat these safeguards, effectively neutering Congress’ effort to restore standards and accountability to the monitoring contract process. HUD has thus not only failed to protect the industry’s smaller businesses (and consumers of affordable housing) from regulatory excesses and abuses, but has actually undermined one of the primarypurposes of the 2000 reform law.

Nevertheless, there were indications, in 2017, that HUD, under Secretary Carson, would begin to reform this process and actually conduct a legitimate procurement for the monitoring function. This included an “Industry Day” meeting for prospective bidders in November 2017 and the division of the monitoring contract into design and production monitoring functions. Now, though, there is disconcerting evidence that HUD could be backsliding on this essential program reform. Specifically, MHARR has learned that the last IBTS monitoring contract, which was due to expire in August 2018, instead of being replacedwith a new, genuinely competitive contract, has instead been extendedfor (at least) one year through a no-bid, sole-source, so-called “bridge” contract.

As objectionable and damaging as this is in itself, for continuing – on a dejurebasis – HUD’s addiction to sole-source procurements for this function, the official HUD “Justification for Other than Full and Open Competition” (Justification Document) for this contract, actually lauds the entrenched incumbent contractor in ways that could indicate that there will be no “full and open” competition for the full-term monitoring contract that succeeds the alleged “bridge” contract. For example, the Justification Document states, among other things: “the depth and breadth of knowledge demonstrated by the contractor [i.e., IBTS] during the performance of the current contract makes them uniquely qualifiedto perform services during the 12-month bridge. *** The contractor’s experience is uniquebecause the contractor has extensive knowledge of working with HUD’s national building code 924 C.F.R. 3280) in areas of code administration and enforcement for several decades.” (Emphasis added).

Such language – coupled with the no-bid, sole-source “bridge” contract itself – indicate that HUD could well have no intention of conducting a legitimate, competitive solicitation for the next monitoring contract that will “drain the swamp” of 40-plus years of abuse. Indeed, such accolades for the entrenched incumbent could become a self-fulfilling prophecy, discouraging other bidders from even competing for the contract, thereby continuing and reinforcing HUD’s multiple violations of applicable law (again, MHARR has searched for, but has been unable to locate, anysimilar instance of such a 40-year-plus dependence on one entrenched defactosole-source contractor) and undermining Secretary Carson’s effort to reform the manufactured housing program. Indeed, legitimate competition, a new monitoring contractor and a monitoring contract that complies with substantive law regarding the limited nature of the monitoring function, are essentialto the successful implementation of any such reforms.

This no-bid, sole-source “bridge” contract is — and should be — totally unacceptable to the entireindustry, and particularly its smaller businesses, as well as consumers of affordable housing.

If the HUD monitoring contract “swamp” is to be “drained,” the time for complying with the law – and finally ensuring full and fair competition for the program monitoring contract – is, emphatically, now.

Mark Weiss

MHARR is a Washington, D.C.-based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

“MHARR-Issues and Perspectives” is available for re-publication in full (i.e., without alteration or substantive modification) without further permission and with proper attribution to MHARR. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]