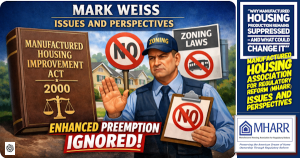

“A Red-Flag Warning for the Manufactured Home Industry and Consumers”

While Washington, D.C. and many, if not most, state capitals are currently fixated on the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences, other dynamics are afoot in the nation’s capital that will inevitably have a profound long-termimpact on the nation as a whole and on the federally-regulated manufactured housing industry. One such dynamic is the approaching presidential election and the surrounding uncertainty as to who the next president of the United States will be. And among the inevitable questions growing out of that uncertainty, is ambiguity regarding the future shape, nature and direction of regulatory policy within the federal government. That inherent uncertainty, however, makes it all the more important that the industry and consumers step-up, right now, to get the maximum advantage and benefit possible from the remainder of President Trump’s first term and the emphasis that he has placed on regulatory reform within the federal government in general and HUD in particular. Thus, MHARR has conducted an in-depth study and analysis of this matter, in order to produce a thorough and up-to-date evaluation of the current status of regulatory reform activity at HUD. The results of that analysis present a clear warning – a “red flag” for both the industry and consumers — that one of the best opportunities to ever exist for real, substantial and concrete regulatory reform, could easily slip away without aggressive, focused, meaningful and forceful action right now.

To be sure, the general contours of federal regulatory policy under a second Trump Administration on the one hand, or a new Biden Administration on the other, are not difficult to discern and predict. Undoubtedly, a re-elected President Trump would continue to pursue — and potentially expand — the type of regulatory reform initiatives that have been the hallmark of his first term. A Biden presidency, on the other hand, would likely see the cessation of those reform activities and a return to, retrenchment — and, again, potential expansion – of the significantly more aggressive regulatory policies (and related regulatory compliance costs) that characterized the Obama Administration. Consequently, the ultimate outcome of the November election will be critical for both HUD Code manufactured housing – as a federally-regulated industry — and for American consumers of affordable housing, going forward.

And while that outcome is unknowable at present, there are matters related to the impending conclusion of President Trump’s first term – with enormous potential implications for both the HUD Code industry and its consumers– that are known and must be dealt-with during the remainder of that term as an urgent priority. These matters – ifsuccessfully completed and implemented over the remaining months of 2020 – could have a profoundly positive impact on the regulatory burdens faced by industry manufacturers and, ultimately, the bottom-line price, affordability and availability of HUD Code manufactured homes for millions of Americans. And even though other major problems and challenges would obviously still continue to exist – including discriminatory/exclusionary zoning and the failure of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, after more than a decade, to legitimately implement the Duty to Serve Underserved Markets (DTS) and provide market-significant support for the vast bulk of HUD Code homebuyers – a substantial reduction in the federal regulatory burdens faced by industry manufacturers would certainly help to boost both the production and utilization of HUD Code housing.

Thus, as the COVID-19 pandemic progresses toward the ultimate phased re-opening of the national economy, the two first-term Trump Administration regulatory reform initiatives that stand to have the greatest impact on the HUD Code industry and consumers of affordable housing – if fully implemented – are the pending “top-to-bottom” review of HUD’s manufactured housing standards and regulations pursuant to Executive Orders (EO) 13771 (“Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs”) and 13777 (“Enforcing the Regulatory Reform Agenda”), and the invalidation of agency “guidance” documents adopted in violation of applicable notice and comment procedures pursuant to Executive Orders 13891 (“Promoting the Rule of Law Through Improved Agency Guidance Documents”) and 13892 (“Promoting the Rule of Law Through Transparency in Civil Administrative Enforcement and Adjudication”).

With a mere seven months remaining before the November election, however, and just nine months remaining before the completion of President Trump’s first term (in January 2021), the current status of these initiatives within HUD is not encouraging and, in fact, is quite disturbing, thus requiring that this entire matter be elevated as a primary focus for the entire industry, for consumers and for the highest-levels of HUD’s senior management.

For example, the “top-to-bottom” review of HUD manufactured housing standards and regulations announced to great fanfare in January 2018 has not yet produced – over a period of nearly two-and-a-half years – the retraction of a single such standard or regulation. Indeed, to date, the only known results of this regulatory reform initiative have been: (1) the May 20, 2019 retraction of 2017 HUD “guidance” regarding the Alternative Construction (AC) treatment of “carport-ready” manufactured homes; and (2) the apparent retraction — and removal from the HUD program website — of thirteen editions of “The Facts” newsletters published by the HUD Office of Manufactured Housing Programs (OMHP) under its former administrator between 2011 and 2017.

That’s it. Two supposed OMHP regulatory reform actions over the entirety (so far) of President Trump’s first term. And one of those actions – the deletion of thirteen non-regulatory newsletters – would count as a regulatory “reform” action only under the broadest imaginable definition and meaning of that term.

Meanwhile, HUD has taken no public action whatsoever with respect to the dozens of specific and much-needed regulatory reform actions (including major reform proposals advanced by MHARR) recommended in 2019 by the statutory Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee (MHCC). Nor has it specifically withdrawn (other than the carport “guidance” memorandum noted above) any of the numerous so-called “guidance” memoranda issued by OMHP under its former administrator, Pamela Danner, without either the prior MHCC review or notice and comment procedures required by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000.

Moreover, the two most recent regulatory reform Executive Orders issued by President Trump, expressly provide that agency “guidance” documents issued without relevant statutory procedures (such as prior MHCC review and notice and comment rulemaking) are not binding on regulated parties and may not even provide non-binding, voluntary “guidance” unless they are published by the issuing agency on a “searchable” internet database. As MHARR has previously noted, though, OMHP has not listed any of its numerous “guidance” documents in the database recently established by HUD for that purpose. Conversely, it has published in that database, Interpretive Bulletins (IBs) adopted by OMHP since 1976. Insofar as IBs, though, are adopted via notice and comment rulemaking, they do not constitute “guidance” documents within the meaning of either of these Executive Orders, and thus, arguably, did not have to be listed at all. As a result, HUD’s “searchable” database includes IBs that are not “guidance,” but omits multiple memoranda that are “guidance,” thus turning the Trump Administration’s “guidance” policy, as expressed in those Executive Orders, on its head.

So, what is the upshot of all this?

First, HUD’s regulatory review under EOs 13771 and 13777 – the centerpiece of the Trump Administration’s regulatory reform agenda – remains incomplete (and potentially in limbo) with respect to manufactured housing regulation, with only minor results thus far, and significant MHCC-recommended reforms hanging in the balance. Meanwhile, time for the completion and – more importantly — the implementation of this review is rapidly running-out and, as MHARR unequivocally warned the industry years ago, an entrenched regulatory and contractor bureaucracy may very well want time to run out. Indeed, the entrenched program “monitoring” contractor, in particular – and as is explained further below — has a financial motive to do everything that it can to run-out-the-clock on any kind of meaningful regulatory reform within the HUD program.

Second, with the single exception of its 2017 carport “guidance” memorandum, not one of HUD’s many sub-regulatory “guidance” documents has been expressly retracted by OMHP or published in HUD’s searchable database. Thus, while those documents are arguably void under the 2000 reform law (including but not limited to section 604(b)(6) of that law, which HUD tried to read out of the law under an “Interpretive Rule” issued by former OMHP administrator William Matchneer), and President Trump’s regulatory reform Executive Orders, it seems that they have been intentionally left in an uncertain legal status by OMHP in order to appear to regulated parties as still being mandatory, binding requirements when, by operation of law, they should not be and, arguably, are not.

Third, insofar as this layer of sub-regulatory OMHP “guidance” documents and other unpublished memoranda, policies, “interpretations” and “Standard Operating Procedures” constitutes the entire alleged basis for virtually all of the intrusive and excessively costly in-plant regulatory activity conducted by HUD’s entrenched “monitoring” contractor, the contractor continues to perform functions that far exceed its legitimate, statutorily-defined and statutorily-limited mission. That mission, as set forth by Congress in the 2000 reform law, is limited to conducting “periodic review[s]” of primary inspection agencies approved by HUD. As MHARR has long-emphasized, though, contractor activity that far exceeds this specific mission, imposes baseless and excessive costs on both HUD Code manufacturers and consumers, while it simultaneously results in excessive and unnecessary costs and funding for HUD’s monitoring contract. Put differently, and as MHARR has often stressed in the past, OMHP’s layer of sub-regulatory “guidance” documents adopted in violation of applicable law, was developed to – and has had the effect of – needlessly, excessively and unlawfully expanding the role, functions and revenues of HUD’s entrenched monitoring contractor to the extreme detriment of both the industry and American consumers of affordable housing.

Indeed, as MHARR has stressed for years, sub-regulatory HUD “guidance” documents –and particularly the mountain of “guidance” documents issued by OMHP without due process related to Subpart I and its change in the fundamental nature of the “monitoring” function – constitute the entire basis for the “make-work” expansion of the program monitoring contract over the past decade. As has been documented by MHARR in submissions to both Congress and HUD, those sub-regulatory “make-work” functions have increased annual monitoring contractor revenues by nearly one hundred percent since 2005, even as industry production, over the same period has declined by more than thirty percent. Thus, there has been a more than 130% upward “swing” in contractor revenues (i.e., the combined impact of increased revenues as compared with work-load), due almost exclusively to the cost of pseudo-regulatory activities arising from sub-regulatory dictates that are clearly unlawful. Significantly, these baseless pseudo-regulatory compliance cost burdens on the industry and homebuyers were all imposed under a succession of non-appointed career program administrators, in itself a blatant violation of the 2000 reform law’s mandate for an appointed, non-career OMHP administrator.

The answer and solution to the decades of abuse that have resulted in this over-blown, over-funded and needlessly costly regulatory (and sub-regulatory) structure, is readily available. It is, quite simply, the timely completion and timely, legitimate implementation – by HUD – of the regulatory reforms mandated by President Trump’s Executive Orders in advance of the November 2020 presidential election. Genuine regulatory reform of the OMHP standards and regulations (and related sub-regulatory actions) as envisioned by the President’s Executive Orders, would help to reduce and control the regulatory compliance costs and burdens shouldered by both manufacturers and consumers, while still maintaining consumer safety as mandated by law. This would expand the availability of manufactured housing as an affordable housing and homeownership resource for millions more Americans, consistent with the purposes and policy of the 2000 reform law.

Unfortunately, though, the industry has wasted more than three years of President Trump’s first term and what is, without question, the most promising opportunity that it has ever had to achieve real and lasting regulatory reform within the HUD manufactured housing program. The current “slow-roll” of the regulatory reform process by the HUD program, its contractors and its other allies, should be a “red flag” and a warning to the industry that this opportunity, without immediate, targeted, aggressive action, could be lost. There is still sufficient time – for now – to change course and move this process forward, but it must be a priority for senior-level decision makers at HUD, within the industry itself (including the Manufactured Housing Institute — MHI), for consumers of affordable housing, and within OMHP (including Administrator Teresa Payne). Put differently, the “crunch-time” for significant action to help both the HUD Code industry and consumers of affordable housing is right now.

Mark Weiss

MHARR is a Washington, D.C.-based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

“MHARR-Issues and Perspectives” is available for re-publication in full (i.e., without alteration or substantive modification) without further permission and with proper attribution to MHARR.

While Washington, D.C. and many, if not most, state capitals are currently fixated on the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences, other dynamics are afoot in the nation’s capital that will inevitably have a profound long-termimpact on the nation as a whole and on the federally-regulated manufactured housing industry. One such dynamic is the approaching presidential election and the surrounding uncertainty as to who the next president of the United States will be. And among the inevitable questions growing out of that uncertainty, is ambiguity regarding the future shape, nature and direction of regulatory policy within the federal government. That inherent uncertainty, however, makes it all the more important that the industry and consumers step-up, right now, to get the maximum advantage and benefit possible from the remainder of President Trump’s first term and the emphasis that he has placed on regulatory reform within the federal government in general and HUD in particular. Thus, MHARR has conducted an in-depth study and analysis of this matter, in order to produce a thorough and up-to-date evaluation of the current status of regulatory reform activity at HUD. The results of that analysis present a clear warning – a “red flag” for both the industry and consumers — that one of the best opportunities to ever exist for real, substantial and concrete regulatory reform, could easily slip away without aggressive, focused, meaningful and forceful action right now.

To be sure, the general contours of federal regulatory policy under a second Trump Administration on the one hand, or a new Biden Administration on the other, are not difficult to discern and predict. Undoubtedly, a re-elected President Trump would continue to pursue — and potentially expand — the type of regulatory reform initiatives that have been the hallmark of his first term. A Biden presidency, on the other hand, would likely see the cessation of those reform activities and a return to, retrenchment — and, again, potential expansion – of the significantly more aggressive regulatory policies (and related regulatory compliance costs) that characterized the Obama Administration. Consequently, the ultimate outcome of the November election will be critical for both HUD Code manufactured housing – as a federally-regulated industry — and for American consumers of affordable housing, going forward.

And while that outcome is unknowable at present, there are matters related to the impending conclusion of President Trump’s first term – with enormous potential implications for both the HUD Code industry and its consumers– that are known and must be dealt-with during the remainder of that term as an urgent priority. These matters – ifsuccessfully completed and implemented over the remaining months of 2020 – could have a profoundly positive impact on the regulatory burdens faced by industry manufacturers and, ultimately, the bottom-line price, affordability and availability of HUD Code manufactured homes for millions of Americans. And even though other major problems and challenges would obviously still continue to exist – including discriminatory/exclusionary zoning and the failure of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, after more than a decade, to legitimately implement the Duty to Serve Underserved Markets (DTS) and provide market-significant support for the vast bulk of HUD Code homebuyers – a substantial reduction in the federal regulatory burdens faced by industry manufacturers would certainly help to boost both the production and utilization of HUD Code housing.

Thus, as the COVID-19 pandemic progresses toward the ultimate phased re-opening of the national economy, the two first-term Trump Administration regulatory reform initiatives that stand to have the greatest impact on the HUD Code industry and consumers of affordable housing – if fully implemented – are the pending “top-to-bottom” review of HUD’s manufactured housing standards and regulations pursuant to Executive Orders (EO) 13771 (“Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs”) and 13777 (“Enforcing the Regulatory Reform Agenda”), and the invalidation of agency “guidance” documents adopted in violation of applicable notice and comment procedures pursuant to Executive Orders 13891 (“Promoting the Rule of Law Through Improved Agency Guidance Documents”) and 13892 (“Promoting the Rule of Law Through Transparency in Civil Administrative Enforcement and Adjudication”).

With a mere seven months remaining before the November election, however, and just nine months remaining before the completion of President Trump’s first term (in January 2021), the current status of these initiatives within HUD is not encouraging and, in fact, is quite disturbing, thus requiring that this entire matter be elevated as a primary focus for the entire industry, for consumers and for the highest-levels of HUD’s senior management.

For example, the “top-to-bottom” review of HUD manufactured housing standards and regulations announced to great fanfare in January 2018 has not yet produced – over a period of nearly two-and-a-half years – the retraction of a single such standard or regulation. Indeed, to date, the only known results of this regulatory reform initiative have been: (1) the May 20, 2019 retraction of 2017 HUD “guidance” regarding the Alternative Construction (AC) treatment of “carport-ready” manufactured homes; and (2) the apparent retraction — and removal from the HUD program website — of thirteen editions of “The Facts” newsletters published by the HUD Office of Manufactured Housing Programs (OMHP) under its former administrator between 2011 and 2017.

That’s it. Two supposed OMHP regulatory reform actions over the entirety (so far) of President Trump’s first term. And one of those actions – the deletion of thirteen non-regulatory newsletters – would count as a regulatory “reform” action only under the broadest imaginable definition and meaning of that term.

Meanwhile, HUD has taken no public action whatsoever with respect to the dozens of specific and much-needed regulatory reform actions (including major reform proposals advanced by MHARR) recommended in 2019 by the statutory Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee (MHCC). Nor has it specifically withdrawn (other than the carport “guidance” memorandum noted above) any of the numerous so-called “guidance” memoranda issued by OMHP under its former administrator, Pamela Danner, without either the prior MHCC review or notice and comment procedures required by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000.

Moreover, the two most recent regulatory reform Executive Orders issued by President Trump, expressly provide that agency “guidance” documents issued without relevant statutory procedures (such as prior MHCC review and notice and comment rulemaking) are not binding on regulated parties and may not even provide non-binding, voluntary “guidance” unless they are published by the issuing agency on a “searchable” internet database. As MHARR has previously noted, though, OMHP has not listed any of its numerous “guidance” documents in the database recently established by HUD for that purpose. Conversely, it has published in that database, Interpretive Bulletins (IBs) adopted by OMHP since 1976. Insofar as IBs, though, are adopted via notice and comment rulemaking, they do not constitute “guidance” documents within the meaning of either of these Executive Orders, and thus, arguably, did not have to be listed at all. As a result, HUD’s “searchable” database includes IBs that are not “guidance,” but omits multiple memoranda that are “guidance,” thus turning the Trump Administration’s “guidance” policy, as expressed in those Executive Orders, on its head.

So, what is the upshot of all this?

First, HUD’s regulatory review under EOs 13771 and 13777 – the centerpiece of the Trump Administration’s regulatory reform agenda – remains incomplete (and potentially in limbo) with respect to manufactured housing regulation, with only minor results thus far, and significant MHCC-recommended reforms hanging in the balance. Meanwhile, time for the completion and – more importantly — the implementation of this review is rapidly running-out and, as MHARR unequivocally warned the industry years ago, an entrenched regulatory and contractor bureaucracy may very well want time to run out. Indeed, the entrenched program “monitoring” contractor, in particular – and as is explained further below — has a financial motive to do everything that it can to run-out-the-clock on any kind of meaningful regulatory reform within the HUD program.

Second, with the single exception of its 2017 carport “guidance” memorandum, not one of HUD’s many sub-regulatory “guidance” documents has been expressly retracted by OMHP or published in HUD’s searchable database. Thus, while those documents are arguably void under the 2000 reform law (including but not limited to section 604(b)(6) of that law, which HUD tried to read out of the law under an “Interpretive Rule” issued by former OMHP administrator William Matchneer), and President Trump’s regulatory reform Executive Orders, it seems that they have been intentionally left in an uncertain legal status by OMHP in order to appear to regulated parties as still being mandatory, binding requirements when, by operation of law, they should not be and, arguably, are not.

Third, insofar as this layer of sub-regulatory OMHP “guidance” documents and other unpublished memoranda, policies, “interpretations” and “Standard Operating Procedures” constitutes the entire alleged basis for virtually all of the intrusive and excessively costly in-plant regulatory activity conducted by HUD’s entrenched “monitoring” contractor, the contractor continues to perform functions that far exceed its legitimate, statutorily-defined and statutorily-limited mission. That mission, as set forth by Congress in the 2000 reform law, is limited to conducting “periodic review[s]” of primary inspection agencies approved by HUD. As MHARR has long-emphasized, though, contractor activity that far exceeds this specific mission, imposes baseless and excessive costs on both HUD Code manufacturers and consumers, while it simultaneously results in excessive and unnecessary costs and funding for HUD’s monitoring contract. Put differently, and as MHARR has often stressed in the past, OMHP’s layer of sub-regulatory “guidance” documents adopted in violation of applicable law, was developed to – and has had the effect of – needlessly, excessively and unlawfully expanding the role, functions and revenues of HUD’s entrenched monitoring contractor to the extreme detriment of both the industry and American consumers of affordable housing.

Indeed, as MHARR has stressed for years, sub-regulatory HUD “guidance” documents –and particularly the mountain of “guidance” documents issued by OMHP without due process related to Subpart I and its change in the fundamental nature of the “monitoring” function – constitute the entire basis for the “make-work” expansion of the program monitoring contract over the past decade. As has been documented by MHARR in submissions to both Congress and HUD, those sub-regulatory “make-work” functions have increased annual monitoring contractor revenues by nearly one hundred percent since 2005, even as industry production, over the same period has declined by more than thirty percent. Thus, there has been a more than 130% upward “swing” in contractor revenues (i.e., the combined impact of increased revenues as compared with work-load), due almost exclusively to the cost of pseudo-regulatory activities arising from sub-regulatory dictates that are clearly unlawful. Significantly, these baseless pseudo-regulatory compliance cost burdens on the industry and homebuyers were all imposed under a succession of non-appointed career program administrators, in itself a blatant violation of the 2000 reform law’s mandate for an appointed, non-career OMHP administrator.

The answer and solution to the decades of abuse that have resulted in this over-blown, over-funded and needlessly costly regulatory (and sub-regulatory) structure, is readily available. It is, quite simply, the timely completion and timely, legitimate implementation – by HUD – of the regulatory reforms mandated by President Trump’s Executive Orders in advance of the November 2020 presidential election. Genuine regulatory reform of the OMHP standards and regulations (and related sub-regulatory actions) as envisioned by the President’s Executive Orders, would help to reduce and control the regulatory compliance costs and burdens shouldered by both manufacturers and consumers, while still maintaining consumer safety as mandated by law. This would expand the availability of manufactured housing as an affordable housing and homeownership resource for millions more Americans, consistent with the purposes and policy of the 2000 reform law.

Unfortunately, though, the industry has wasted more than three years of President Trump’s first term and what is, without question, the most promising opportunity that it has ever had to achieve real and lasting regulatory reform within the HUD manufactured housing program. The current “slow-roll” of the regulatory reform process by the HUD program, its contractors and its other allies, should be a “red flag” and a warning to the industry that this opportunity, without immediate, targeted, aggressive action, could be lost. There is still sufficient time – for now – to change course and move this process forward, but it must be a priority for senior-level decision makers at HUD, within the industry itself (including the Manufactured Housing Institute — MHI), for consumers of affordable housing, and within OMHP (including Administrator Teresa Payne). Put differently, the “crunch-time” for significant action to help both the HUD Code industry and consumers of affordable housing is right now.

Mark Weiss

MHARR is a Washington, D.C.-based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

“MHARR-Issues and Perspectives” is available for re-publication in full (i.e., without alteration or substantive modification) without further permission and with proper attribution to MHARR.