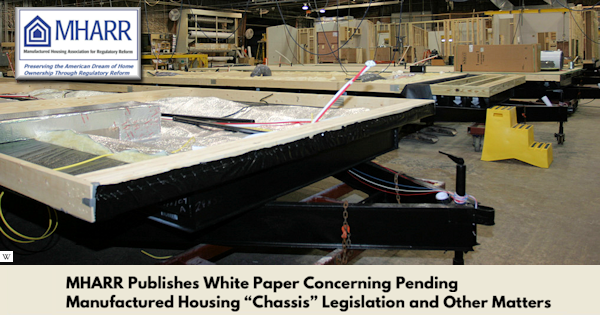

MHARR Publishes White Paper Concerning Pending Manufactured Housing “Chassis” Legislation and Other Matters

MHARR POSITION PAPER AND PLAN OF ACTION ON TWO PENDING LEGISLATIVE PROPOSALS REGARDING DELETION OF THE “PERMANENT CHASSIS” REQUIREMENT AND OTHER MATTERS

RESEARCHED AND PREPARED BY THE MANUFACTURED HOUSING ASSOCIATION FOR REGULATORY REFORM

SEPTEMBER 2023

I. INTRODUCTION

A “discussion draft” of housing legislation circulated by Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) as well as a stand-alone bill, H.R. 5198, introduced by Tennessee Rep. John Rose (R-TN6), have raised serious concerns regarding both their intent and potential impact on manufactured housing regulation, the manufactured housing market and American consumers of affordable housing.

The Senate discussion draft, entitled “Renewing Opportunity in the American Dream to Housing Act” (ROAD to Housing Act), was publicly released by Senator Scott, the Ranking Member of the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee, on April 26, 2023. The draft bill includes two sets of provisions affecting manufactured housing. One set of provisions relates to issues arising out of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law and SAFE Act that have been a perennial issue for the Berkshire Hathaway and Clayton Homes, Inc.-affiliated lenders, 21st Mortgage, Inc. (21st) and Vanderbilt Mortgage Corporation (Vanderbilt). The other would remove the requirement for a “permanent chassis” that is part of the definition of “manufactured home” contained in both the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 (42 U.S.C. 5401, et seq.) as amended by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law) and related implementing regulations. The “permanent chassis” requirement has been part of the legislative and regulatory “manufactured home” definitions since they were first adopted nearly 50 years ago.

The ”parallel” house bill, H.R. 5198, the “Expansion of Attainable Homeownership Through Manufactured Housing Act of 2023,” introduced on August 11, 2023, by House Financial Services Committee member John Rose, does not address the finance-related matters included in the Scott discussion draft and, at present, pertains only to the removal of the permanent chassis requirement contained in extant federal law.

While MHARR supports the surgical deletion of the permanent chassis requirement contained in 42 U.S.C. 5402(6) (i.e., the five-word clause “built on a permanent chassis”) – without any other change, addition or deletion to the 1974 Act as amended (as it has for its entire organizational existence since 1985), extreme caution is needed to ensure that this modification is not altered or undermined during the legislative process, and also to ensure that the legislative (and/or regulatory) process is not abused to otherwise alter or amend federal manufactured housing law or regulations to the detriment of either mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing or mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing consumers. If such abuse were to infiltrate the legislative or regulatory processes, the potential impacts of these changes could be extremely far-reaching and could include significant unintended (and potentially negative) consequences. Consequently, while MHARR supports the surgical deletion of the permanent chassis requirement only, it would strongly oppose any extraneous effort to alter or modify the law or regulations governing the federal regulation of manufactured housing construction and safety.

II. BRIEF HISTORY

The “permanent chassis” requirement has been part of the 42 U.S.C. 5402(6) definition of “manufactured home” since the federal authorizing law was first enacted in 1974 and has similarly been incorporated within the HUD regulatory definition of manufactured home since the inception of federal regulation in 1976. Almost immediately, however, the clause was rendered an anachronism by technological advances which allowed the chassis to be incorporated into the home structure itself. This allowed the transportation frame and wheels to be more easily removed from the home, making installation of the home on a permanent foundation easier and less costly. As a result, the industry, beginning in the mid and late-1980s, undertook efforts to delete the permanent chassis mandate. Initially, the industry filed legal action against HUD to invalidate the permanent chassis requirement after HUD stopped industry firms within the post-production sector from removing the chassis of homes being installed. That effort, however, was not successful.

Subsequently, in the early 1990s, the industry supported proposed legislation – the so-called Hiler Amendment, sponsored by then-Rep. John Hiler (R-IN3) which would have deleted the permanent chassis mandate among other program reforms. Ultimately, however, that provision was deleted from the bill in a House-Senate conference committee at the end of the legislative process.

Consequently, despite these industry efforts, the permanent chassis requirement has remained in the law, notwithstanding the acknowledged fact that from a technical and engineering perspective, the mandate is unnecessary and imposes needless costs on consumers of HUD-regulated manufactured housing.

It should be noted, however, that with regard to both of these past efforts to delete the permanent chassis provision, both the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) – representing site-builders – aggressively opposed removal of the chassis requirement (as addressed in greater detail below) and affirmatively sought to ensure its continued presence in the federal manufactured housing regulatory statute.

III. ANALYSIS

- FINANCE-RELATED PROVISIONS OF THE ROAD TO HOUSING DRAFT

The finance-related provisions of Senator Scott’s discussion draft would require the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to issue “updated” regulations to: (1) “allow for salaried originators of residential mortgage loans that only originate small dollar mortgages;” and (2) to “amend … limitations with respect to points and fees … to encourage additional lending for small dollar mortgages.” “Small dollar mortgages” are defined in the draft bill (in part) as “mortgage loans having an original principal obligation of not more than $70,000.”

The current loan “originator” prohibition contained in federal law, was adopted in response to complaints from consumer groups that salaried employees of manufactured home retailers were “steering” customers to higher-priced or otherwise disadvantageous loans under the guise of providing loan application assistance. Points and fees meanwhile, are relevant to determining whether a home loan is a “high-cost loan” under Dodd-Frank (and the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act – “HOEPA”), exposing the lender to potential penalties and liability exposure, among other things.

These two consumer finance-related issues were highlighted repeatedly by 21st,Vanderbilt and the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI), in seeking and promoting prior legislation to amend Dodd-Frank. And, in fact, a statutory amendment to sidestep the loan originator prohibition was enacted into law in 2018 (having been signed by President Trump). But now, these same two provisions (albeit framed as a regulatory amendment and pegged to a no longer market-relevant $70,000 ceiling) are both incorporated in the draft ROAD to Housing Act. Why they have been included in the ROAD to Housing Act is unclear, as is their relevance or necessity given intervening changes in the HUD Code market.

Indeed, it would be far more beneficial to the entire industry and consumers of affordable housing, if these narrowly targeted “gift” provisions for the industry’s dominant lenders, were either replaced or supplemented by an amendment that would change the word “may,” as used in current law with respect to serving manufactured home chattel loans under the Duty to Serve (DTS) mandate, to “shall.” This is particularly the case insofar as MHI publicly cited this as an issue at a July 18, 2023 DTS “Listening Session” conducted by DTS’ federal enforcer, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). Through this action, MHI has provided Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with a ready excuse and rationalization for their failure to include chattel manufactured housing loans within their DTS implementation programs. By contrast, changing this language would leave no doubt that Congress – some 15 years after the adoption of the DTS directive – expects and requires that the dominant manufactured home consumer chattel market be fully served, in a market-significant manner, under DTS. Such an amendment would produce tangible benefits for the vast bulk of manufactured housing consumers who have been left totally unserved under the current DTS statutory language and corresponding failure of implementation by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

These are just the first, though, of multiple questions that are raised by the discussion draft and H.R. 5198 with respect to the most fundamental aspects of manufactured housing and its regulation. In fact, the more closely one looks into the discussion draft and H.R. 5198, and their potential impacts, the more one realizes the degree of confusion and potentially serious problems and detrimental unintended consequences that could follow from their adoption.

- DELETION OF “PERMANENT CHASSIS” REQUIREMENT

MHARR, as explained above, has – and continues to – support the surgical deletion of the permanent chassis requirement, with no other changes and with appropriate congressional guarantees. And while MHARR’s support for this position has been consistent since its establishment, it must be noted that the housing market was far different 40 years ago (or even 20 years ago) than it is today. In the past, there was no such thing as “tiny homes” or the widespread use of recreational vehicles, park models and other types of structures as permanent (and temporary) dwellings. As a result, removal of the permanent chassis requirement at that time would not have led to massive confusion over the lines of demarcation between different types of homes and which jurisdiction or jurisdictions would have regulatory authority over their construction, placement and installation. NAHB claimed that it would when the issue was litigated in the mid-1980s, but that was more a matter of fear over the competitive advantages of HUD Code manufactured housing than any legitimate concern over genuine confusion between manufactured and site-built housing. But that is not the case today.

Today, powerful forces, such as the International Code Council (ICC) – and others, including some within the HUD Code manufactured housing industry, such as Berkshire Hathaway-owned Clayton Homes, Inc – are openly promoting the widespread use and recognition of “off-site construction” “off-site structures,” “off-site buildings,” “off-site homes” and other variants as a source of residential housing.

And what does so-called “off-site” construction include, according to these sources? According to ICC, so-called “off-site” construction, as addressed at a June 2023 “Off-Site Construction Summit” in Washington, D.C., includes “panelized systems,” “manufactured homes,” “tiny houses,” recreational vehicles, “modular/pods” and “shipping containers,” among other things. ICC, moreover, has developed model codes for the regulation of multiple types of so-called “off-site” structures, including modular homes and “tiny homes,” among others.

The introduction of the term “off-site” construction into the housing lexicon thus raises the first – and most critical set of questions and red flags regarding the two potential chassis removal bills. And that is, what exactly is so-called “off-site” construction? Historically, in the United States, there have been only two methods of residential single-family dwelling construction, namely site-built homes and factory-built homes. Site-built homes are homes built with all raw materials delivered to and constructed on-site. Such on-site homes have historically been built to and inspected in accordance with state and/or local building codes based on the International Residential Code (IRC). Factory-built homes, on the other hand, because of transportation, affordability and other factors, are built in a factory and then delivered to a site either whole or in sections. Such structures include manufactured homes — which are built to and inspected in accordance with federal HUD standards and regulations – as well as modular homes, sectional homes, “prefab” homes, tiny homes and others built to and inspected in accordance with the IRC, and even temporary living structures including recreational vehicles and park models built in accordance with private “codes” maintained by the Recreational Vehicle Industry Association (RVIA).

Recently, however, certain self-interested parties have begun to use the term “off-site” construction, and have put whatever types of construction they wish under that legally undefined label, from manufactured housing to shipping containers. The question, then, is “why?” Why, suddenly, has so-called “off-site” construction become so critical to all of these self-interested parties?

Given this effort to blur the lines between comprehensively federally-regulated manufactured homes and other types of so-called “off-site” residential construction, removal of the “permanent chassis” requirement – today, if not done surgically and in isolation — could cause widespread chaos and confusion, not only within the housing market, but with regard to the lines of demarcation and authority over the regulation and use of different types of so-called “off-site” residential construction. Further, and more importantly, just who stands to benefit from any such chaos and confusion, including, but not limited to, confusion over – and potential changes to — the regulation of different types of these so-called off-site products? Put differently, given today’s more diversified housing market, what is the potential downside of removal of the permanent chassis requirement for mainstream, non-subsidized manufactured housing, and is there a bait and switch involved with this fundamental change in the law given the self-interest of the various participants?

For now, there are more questions than answers. But the answers, ultimately, will be extremely important, as they could well determine the entire future of the federally-regulated manufactured housing market and especially the industry’s most affordable mainstream homes, which are currently protected, defended and advanced by the minimum (base) standards of the HUD Code.

What, then, would happen if the term “off-site” construction, or some similar variant, were inserted into the HUD regulatory statute during the legislative process triggered by the pending discussion draft and bill? Similarly, what would happen if a specific proprietary term or any other ill-intended term were included during that process? Or, worse yet, what would happen if any such term or terms were included in HUD’s standards and regulations concerning manufactured housing?

If either (or any) of these scenarios were to occur, what would happen to today’s base standards for manufactured housing? Would they be made more stringent and costly to meet pre-existing criteria for more costly types of so-called “off-site” construction? Would they be ratcheted-up to be more consistent with the criteria for those so-called “off-site” products? And if the standards were hiked-up to astronomically costly levels, as they likely would be, what would then happen to the most affordable types of mainstream HUD Code manufactured homes which currently constitute approximately 80% of the HUD Code manufactured housing market? Presumably, they would disappear in favor of the more costly homes favored by the industry’s dominant producers. And with them, would disappear not only the manufacturers of those affordable homes, but also the nation’s most affordable source of non-subsidized homeownership for lower and moderate-income families.

Alternatively, what would happen if the proponents of confusion between federally-regulated manufactured housing and other types of so-called off-site structures (many if not all of which compete with HUD Code manufactured housing) were to use the legislative (and/or regulatory) processes triggered by the pending legislation to push for the end of the HUD manufactured housing program? What would happen if those self-interested parties tried to end preemptive federal regulation over manufactured housing and return such regulation to the states? What would happen if those self-interested parties tried to tie state regulation over manufactured housing to some dominant role for ICC – either in the development of a model manufactured housing code or some type of continuing enforcement role?

While considering these questions, it is worth pointing out that HUD and NAHB, both of which aggressively opposed the removal of the “permanent chassis” requirement from the manufactured housing statute in the 1980s and 1990s are somehow strangely silent now concerning the pending bills. Could it be that one or both are silent partners in this effort to sow chaos and confusion – or worse? Could it be that HUD either wants to expand the scope of its control or, conversely, jettison the federal manufactured housing program altogether? Could it be that NAHB wants to get in on the potential benefits of federal preemption for “tiny homes” and other types of so-called “off-site” construction? Neither these or any number of other potential subversions would be good news for either the HUD Code industry or its consumers. Yet all would be potential threats during both the legislative and regulatory processes.

All of which begs the question – in the highly-charged competitive atmosphere that HUD Code homes and HUD Code manufacturers face with respect to multiple other types of so-called “off-site” construction, is now really the time to open the fundamental definition of “manufactured home” to a process that could have unexpected twists and turns and equally unexpected but devastating consequences?

IV. CONCLUSION

While MHARR supports the surgical removal of the permanent chassis requirement as explained above, there are major hazards at every turn in such a process and self-interested players with untold millions of dollars hanging in the balance that would like nothing better than to sabotage competitors and “reinvent” manufactured housing in their own proprietary image. Before the industry takes the bait, it had better get specific answers to these most fundamental and basic questions.

MHARR is a Washington, D.C.-based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

This Report and Analysis is available for re-publication in full (i.e., without alteration or substantive modification) without further permission and with proper attribution.

MHARR POSITION PAPER AND PLAN OF ACTION ON TWO PENDING LEGISLATIVE PROPOSALS REGARDING DELETION OF THE “PERMANENT CHASSIS” REQUIREMENT AND OTHER MATTERS

RESEARCHED AND PREPARED BY THE MANUFACTURED HOUSING ASSOCIATION FOR REGULATORY REFORM

SEPTEMBER 2023

I. INTRODUCTION

A “discussion draft” of housing legislation circulated by Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) as well as a stand-alone bill, H.R. 5198, introduced by Tennessee Rep. John Rose (R-TN6), have raised serious concerns regarding both their intent and potential impact on manufactured housing regulation, the manufactured housing market and American consumers of affordable housing.

The Senate discussion draft, entitled “Renewing Opportunity in the American Dream to Housing Act” (ROAD to Housing Act), was publicly released by Senator Scott, the Ranking Member of the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee, on April 26, 2023. The draft bill includes two sets of provisions affecting manufactured housing. One set of provisions relates to issues arising out of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law and SAFE Act that have been a perennial issue for the Berkshire Hathaway and Clayton Homes, Inc.-affiliated lenders, 21st Mortgage, Inc. (21st) and Vanderbilt Mortgage Corporation (Vanderbilt). The other would remove the requirement for a “permanent chassis” that is part of the definition of “manufactured home” contained in both the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 (42 U.S.C. 5401, et seq.) as amended by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law) and related implementing regulations. The “permanent chassis” requirement has been part of the legislative and regulatory “manufactured home” definitions since they were first adopted nearly 50 years ago.

The ”parallel” house bill, H.R. 5198, the “Expansion of Attainable Homeownership Through Manufactured Housing Act of 2023,” introduced on August 11, 2023, by House Financial Services Committee member John Rose, does not address the finance-related matters included in the Scott discussion draft and, at present, pertains only to the removal of the permanent chassis requirement contained in extant federal law.

While MHARR supports the surgical deletion of the permanent chassis requirement contained in 42 U.S.C. 5402(6) (i.e., the five-word clause “built on a permanent chassis”) – without any other change, addition or deletion to the 1974 Act as amended (as it has for its entire organizational existence since 1985), extreme caution is needed to ensure that this modification is not altered or undermined during the legislative process, and also to ensure that the legislative (and/or regulatory) process is not abused to otherwise alter or amend federal manufactured housing law or regulations to the detriment of either mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing or mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing consumers. If such abuse were to infiltrate the legislative or regulatory processes, the potential impacts of these changes could be extremely far-reaching and could include significant unintended (and potentially negative) consequences. Consequently, while MHARR supports the surgical deletion of the permanent chassis requirement only, it would strongly oppose any extraneous effort to alter or modify the law or regulations governing the federal regulation of manufactured housing construction and safety.

II. BRIEF HISTORY

The “permanent chassis” requirement has been part of the 42 U.S.C. 5402(6) definition of “manufactured home” since the federal authorizing law was first enacted in 1974 and has similarly been incorporated within the HUD regulatory definition of manufactured home since the inception of federal regulation in 1976. Almost immediately, however, the clause was rendered an anachronism by technological advances which allowed the chassis to be incorporated into the home structure itself. This allowed the transportation frame and wheels to be more easily removed from the home, making installation of the home on a permanent foundation easier and less costly. As a result, the industry, beginning in the mid and late-1980s, undertook efforts to delete the permanent chassis mandate. Initially, the industry filed legal action against HUD to invalidate the permanent chassis requirement after HUD stopped industry firms within the post-production sector from removing the chassis of homes being installed. That effort, however, was not successful.

Subsequently, in the early 1990s, the industry supported proposed legislation – the so-called Hiler Amendment, sponsored by then-Rep. John Hiler (R-IN3) which would have deleted the permanent chassis mandate among other program reforms. Ultimately, however, that provision was deleted from the bill in a House-Senate conference committee at the end of the legislative process.

Consequently, despite these industry efforts, the permanent chassis requirement has remained in the law, notwithstanding the acknowledged fact that from a technical and engineering perspective, the mandate is unnecessary and imposes needless costs on consumers of HUD-regulated manufactured housing.

It should be noted, however, that with regard to both of these past efforts to delete the permanent chassis provision, both the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) – representing site-builders – aggressively opposed removal of the chassis requirement (as addressed in greater detail below) and affirmatively sought to ensure its continued presence in the federal manufactured housing regulatory statute.

III. ANALYSIS

- FINANCE-RELATED PROVISIONS OF THE ROAD TO HOUSING DRAFT

The finance-related provisions of Senator Scott’s discussion draft would require the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to issue “updated” regulations to: (1) “allow for salaried originators of residential mortgage loans that only originate small dollar mortgages;” and (2) to “amend … limitations with respect to points and fees … to encourage additional lending for small dollar mortgages.” “Small dollar mortgages” are defined in the draft bill (in part) as “mortgage loans having an original principal obligation of not more than $70,000.”

The current loan “originator” prohibition contained in federal law, was adopted in response to complaints from consumer groups that salaried employees of manufactured home retailers were “steering” customers to higher-priced or otherwise disadvantageous loans under the guise of providing loan application assistance. Points and fees meanwhile, are relevant to determining whether a home loan is a “high-cost loan” under Dodd-Frank (and the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act – “HOEPA”), exposing the lender to potential penalties and liability exposure, among other things.

These two consumer finance-related issues were highlighted repeatedly by 21st,Vanderbilt and the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI), in seeking and promoting prior legislation to amend Dodd-Frank. And, in fact, a statutory amendment to sidestep the loan originator prohibition was enacted into law in 2018 (having been signed by President Trump). But now, these same two provisions (albeit framed as a regulatory amendment and pegged to a no longer market-relevant $70,000 ceiling) are both incorporated in the draft ROAD to Housing Act. Why they have been included in the ROAD to Housing Act is unclear, as is their relevance or necessity given intervening changes in the HUD Code market.

Indeed, it would be far more beneficial to the entire industry and consumers of affordable housing, if these narrowly targeted “gift” provisions for the industry’s dominant lenders, were either replaced or supplemented by an amendment that would change the word “may,” as used in current law with respect to serving manufactured home chattel loans under the Duty to Serve (DTS) mandate, to “shall.” This is particularly the case insofar as MHI publicly cited this as an issue at a July 18, 2023 DTS “Listening Session” conducted by DTS’ federal enforcer, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). Through this action, MHI has provided Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with a ready excuse and rationalization for their failure to include chattel manufactured housing loans within their DTS implementation programs. By contrast, changing this language would leave no doubt that Congress – some 15 years after the adoption of the DTS directive – expects and requires that the dominant manufactured home consumer chattel market be fully served, in a market-significant manner, under DTS. Such an amendment would produce tangible benefits for the vast bulk of manufactured housing consumers who have been left totally unserved under the current DTS statutory language and corresponding failure of implementation by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

These are just the first, though, of multiple questions that are raised by the discussion draft and H.R. 5198 with respect to the most fundamental aspects of manufactured housing and its regulation. In fact, the more closely one looks into the discussion draft and H.R. 5198, and their potential impacts, the more one realizes the degree of confusion and potentially serious problems and detrimental unintended consequences that could follow from their adoption.

- DELETION OF “PERMANENT CHASSIS” REQUIREMENT

MHARR, as explained above, has – and continues to – support the surgical deletion of the permanent chassis requirement, with no other changes and with appropriate congressional guarantees. And while MHARR’s support for this position has been consistent since its establishment, it must be noted that the housing market was far different 40 years ago (or even 20 years ago) than it is today. In the past, there was no such thing as “tiny homes” or the widespread use of recreational vehicles, park models and other types of structures as permanent (and temporary) dwellings. As a result, removal of the permanent chassis requirement at that time would not have led to massive confusion over the lines of demarcation between different types of homes and which jurisdiction or jurisdictions would have regulatory authority over their construction, placement and installation. NAHB claimed that it would when the issue was litigated in the mid-1980s, but that was more a matter of fear over the competitive advantages of HUD Code manufactured housing than any legitimate concern over genuine confusion between manufactured and site-built housing. But that is not the case today.

Today, powerful forces, such as the International Code Council (ICC) – and others, including some within the HUD Code manufactured housing industry, such as Berkshire Hathaway-owned Clayton Homes, Inc – are openly promoting the widespread use and recognition of “off-site construction” “off-site structures,” “off-site buildings,” “off-site homes” and other variants as a source of residential housing.

And what does so-called “off-site” construction include, according to these sources? According to ICC, so-called “off-site” construction, as addressed at a June 2023 “Off-Site Construction Summit” in Washington, D.C., includes “panelized systems,” “manufactured homes,” “tiny houses,” recreational vehicles, “modular/pods” and “shipping containers,” among other things. ICC, moreover, has developed model codes for the regulation of multiple types of so-called “off-site” structures, including modular homes and “tiny homes,” among others.

The introduction of the term “off-site” construction into the housing lexicon thus raises the first – and most critical set of questions and red flags regarding the two potential chassis removal bills. And that is, what exactly is so-called “off-site” construction? Historically, in the United States, there have been only two methods of residential single-family dwelling construction, namely site-built homes and factory-built homes. Site-built homes are homes built with all raw materials delivered to and constructed on-site. Such on-site homes have historically been built to and inspected in accordance with state and/or local building codes based on the International Residential Code (IRC). Factory-built homes, on the other hand, because of transportation, affordability and other factors, are built in a factory and then delivered to a site either whole or in sections. Such structures include manufactured homes — which are built to and inspected in accordance with federal HUD standards and regulations – as well as modular homes, sectional homes, “prefab” homes, tiny homes and others built to and inspected in accordance with the IRC, and even temporary living structures including recreational vehicles and park models built in accordance with private “codes” maintained by the Recreational Vehicle Industry Association (RVIA).

Recently, however, certain self-interested parties have begun to use the term “off-site” construction, and have put whatever types of construction they wish under that legally undefined label, from manufactured housing to shipping containers. The question, then, is “why?” Why, suddenly, has so-called “off-site” construction become so critical to all of these self-interested parties?

Given this effort to blur the lines between comprehensively federally-regulated manufactured homes and other types of so-called “off-site” residential construction, removal of the “permanent chassis” requirement – today, if not done surgically and in isolation — could cause widespread chaos and confusion, not only within the housing market, but with regard to the lines of demarcation and authority over the regulation and use of different types of so-called “off-site” residential construction. Further, and more importantly, just who stands to benefit from any such chaos and confusion, including, but not limited to, confusion over – and potential changes to — the regulation of different types of these so-called off-site products? Put differently, given today’s more diversified housing market, what is the potential downside of removal of the permanent chassis requirement for mainstream, non-subsidized manufactured housing, and is there a bait and switch involved with this fundamental change in the law given the self-interest of the various participants?

For now, there are more questions than answers. But the answers, ultimately, will be extremely important, as they could well determine the entire future of the federally-regulated manufactured housing market and especially the industry’s most affordable mainstream homes, which are currently protected, defended and advanced by the minimum (base) standards of the HUD Code.

What, then, would happen if the term “off-site” construction, or some similar variant, were inserted into the HUD regulatory statute during the legislative process triggered by the pending discussion draft and bill? Similarly, what would happen if a specific proprietary term or any other ill-intended term were included during that process? Or, worse yet, what would happen if any such term or terms were included in HUD’s standards and regulations concerning manufactured housing?

If either (or any) of these scenarios were to occur, what would happen to today’s base standards for manufactured housing? Would they be made more stringent and costly to meet pre-existing criteria for more costly types of so-called “off-site” construction? Would they be ratcheted-up to be more consistent with the criteria for those so-called “off-site” products? And if the standards were hiked-up to astronomically costly levels, as they likely would be, what would then happen to the most affordable types of mainstream HUD Code manufactured homes which currently constitute approximately 80% of the HUD Code manufactured housing market? Presumably, they would disappear in favor of the more costly homes favored by the industry’s dominant producers. And with them, would disappear not only the manufacturers of those affordable homes, but also the nation’s most affordable source of non-subsidized homeownership for lower and moderate-income families.

Alternatively, what would happen if the proponents of confusion between federally-regulated manufactured housing and other types of so-called off-site structures (many if not all of which compete with HUD Code manufactured housing) were to use the legislative (and/or regulatory) processes triggered by the pending legislation to push for the end of the HUD manufactured housing program? What would happen if those self-interested parties tried to end preemptive federal regulation over manufactured housing and return such regulation to the states? What would happen if those self-interested parties tried to tie state regulation over manufactured housing to some dominant role for ICC – either in the development of a model manufactured housing code or some type of continuing enforcement role?

While considering these questions, it is worth pointing out that HUD and NAHB, both of which aggressively opposed the removal of the “permanent chassis” requirement from the manufactured housing statute in the 1980s and 1990s are somehow strangely silent now concerning the pending bills. Could it be that one or both are silent partners in this effort to sow chaos and confusion – or worse? Could it be that HUD either wants to expand the scope of its control or, conversely, jettison the federal manufactured housing program altogether? Could it be that NAHB wants to get in on the potential benefits of federal preemption for “tiny homes” and other types of so-called “off-site” construction? Neither these or any number of other potential subversions would be good news for either the HUD Code industry or its consumers. Yet all would be potential threats during both the legislative and regulatory processes.

All of which begs the question – in the highly-charged competitive atmosphere that HUD Code homes and HUD Code manufacturers face with respect to multiple other types of so-called “off-site” construction, is now really the time to open the fundamental definition of “manufactured home” to a process that could have unexpected twists and turns and equally unexpected but devastating consequences?

IV. CONCLUSION

While MHARR supports the surgical removal of the permanent chassis requirement as explained above, there are major hazards at every turn in such a process and self-interested players with untold millions of dollars hanging in the balance that would like nothing better than to sabotage competitors and “reinvent” manufactured housing in their own proprietary image. Before the industry takes the bait, it had better get specific answers to these most fundamental and basic questions.

MHARR is a Washington, D.C.-based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

This Report and Analysis is available for re-publication in full (i.e., without alteration or substantive modification) without further permission and with proper attribution.