MHARR – ISSUES AND PERSPECTIVES

By Mark Weiss

AUGUST 2025

“MORE RED FLAGS FOR THE INDUSTRY AND CONSUMERS IN THE SECOND TRUMP ADMINISTRATION”

In the January 2025 “MHARR Issues and Perspectives” article, entitled “Trump 2.0 – The Industry’s Second Chance,” MHARR stressed that the industry (i.e., the broader industry, represented by the Manufactured Housing Institute), during the first term of Donald Trump’s presidency, had missed a golden opportunity to address and correct – once and for all – the major policy/regulatory bottlenecks that have combined to needlessly stunt the growth and continuing evolution of the HUD Code manufactured housing industry for far too long. Citing those bottlenecks – (1) the discriminatory zoning exclusion of manufactured housing and (2) the discriminatory absence of federal support for competitive manufactured home consumer lending under the Duty to Serve (DTS) mandate, as well as (3) excessive and baseless “energy conservation” regulation through the U.S. Department of Energy, MHARR stated: “… [T]he broader industry, through [the Manufactured Housing Institute] … wasted the four years of the first Trump Administration with endless posturing” and little, or nothing, in the way of concrete results that actually reached the ground to benefit both manufactured housing consumers and the industry itself.

Based on this observation, MHARR emphasized that a second Trump Administration –then just starting — would provide the industry as a whole with “a remarkable second chance” to change course and finally confront, directly and aggressively, the substance of the bottlenecks restraining its growth and expansion, rather than engaging in activities or posturing with little or no real-world market impact. Rather, MHARR said at the time, “it is up to the entire industry and all of its representatives to seek, demand, and achieve the reforms” needed to eliminate those bottlenecks, “that are clearly needed to unleash the industry’s full potential and cement its place as the nation’s premier source of affordable non-subsidized homeownership.”

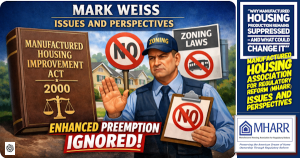

MHARR’s perspective was validated and confirmed when President Trump and HUD Secretary Scott Turner later unveiled their fundamental policy vision to address, correct and resolve the nation’s housing crisis through a strong emphasis on promoting the availability of affordable homeownership. MHARR immediately welcomed this logical and commonsense approach, aligning its own efforts and emphasis with that of President Trump and Secretary Turner, and, at a meeting with Secretary Turner on March 25, 2025, strongly emphasized the point that America’s affordable housing crisis cannot, and will not be resolved without the full utilization and inclusion of affordable, federally-regulated, mainstream manufactured homes. At that meeting, therefore, MHARR pressed for – and will continue to aggressively seek – the elimination of all the long-term bottlenecks suppressing the industry, but most particularly discriminatory and exclusionary zoning, based on relevant provisions of the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law).

Meanwhile, with seven months having now passed since that MHARR article was published and since the beginning of the second Trump Administration, where does the broader industry stand? Have the fundamental reform opportunities presented by a second Trump Administration been realized, or even pursued in any meaningful way? Have the principal bottlenecks to significant industry growth and expansion been rectified, or even addressed? The answer, for the broader industry, is sadly and depressingly familiar.

To start, the objective evidence (i.e., production statistics) shows that the industry remains essentially mired in a stagnant production posture. Since 2017, average annual production of new manufactured homes has varied within approximately +/- 10% of 100,000 homes, from a low (over that period) of 89,169 homes in 2023, to a high of 112,882 in 2022. Most recently, annual production for 2024 was 103,314 homes, and has continued at roughly the same pace during 2025, although the May 2025 statistics reflected a year-over-year monthly decline for the first time since late 2023.

Thus, while these numbers reflect a certain degree of improvement since the industry’s modern-day production low of 49,683 homes in 2009, they have run consistently and significantly lower than the average annual production that prevailed in the years just before the 2009 collapse. For example, average annual production over the ten-year period from 1996 to 2005 was 245,566 homes, while average annual production over the ten-year period from 2015 to 2024 was 94,128 homes, a decline of 62%. Consequently, even with the incremental production rebound that has occurred over the past ten years, the industry has still consistently failed to meet or exceed production levels that were routine just 20-30 years ago. And all of this is occurring against the backdrop of an affordable housing crisis in the United States, with a chronic shortage of as much as 7 million affordable “starter” homes, according to multiple sources.

As MHARR emphasized in the January 2025 “Issues and Perspectives,” the key to breaking out of this long-term malaise, especially during a second Trump Administration with a policy emphasis on assuring the availability of affordable private sector housing, is not to aim for relatively easy “low hanging fruit,” but instead to take bold action to rid the industry and its consumers of the long-term and highly debilitating zoning and consumer financing bottlenecks that have hobbled the industry on a nationwide basis, suppressing production and sales levels for years.

And has this happened on an industry-wide level? No (or, at least, not yet). Instead of going to, and attacking, the root (or, more accurately, roots) of the problem, which would admittedly be difficult and challenging, the industry’s “umbrella” national organization, MHI, has instead chosen to focus its efforts to date on perhaps the lowest of the “low-hanging fruit,” i.e., dropping the long outdated “permanent chassis” requirement from the definition of “manufactured home” contained in the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 – an issue that has been on the “radar-screen,” on and off, for at least four decades.

That’s right. In the 1980s, not long after MHARR was established, there was an effort in Congress, led by MHARR, to delete the “permanent chassis” requirement that had been incorporated into the original 1974 law. Such a provision, contained in the so-called “Hiler Amendment” (named for its principal House of Representatives sponsor, Rep. John Hiler) was ultimately included in the House version of the 1990 housing bill. MHI, under pressure from its members, initially supported the amendment, but later withdrew that support just prior to consideration of the amendment by a House-Senate conference committee. Thus, the Hiler amendment failed, and the chassis issue has persisted since then.

Now, though, with some of its largest corporate conglomerate members seemingly intent on blurring the lines between types of homes and different types of production (as reflected in the ambiguous “attainable” versus “affordable” housing and ”off-site” versus “factory-built” terminology), and seemingly fixated on creating markets for higher-priced, high-end manufactured housing (like so-called “cross-mod” homes) as contrasted with affordable, mainstream HUD Code homes, MHI is now trying to eliminate the term “permanent chassis.” Thus, it backed (as did MHARR) a proposal presented to the Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee (MHCC) on very short notice in June 2025, to eliminate the regulatory “permanent chassis” requirement in Part 3280 for the upper floors of multi-story manufactured homes.

At the same time, it is backing legislation now moving in the Senate, to remove the “permanent chassis” requirement in federal manufactured housing law and make it optional instead. That legislation, incorporated in Senator Tim Scott’s “ROAD to Housing” bill, was approved by the Senate Banking Committee on July 29, 2025, but also contains potentially problematic aspects that MHARR plans to address in detail in a soon-to-be-published analysis.

At the policy level, though, while MHARR has continued to support the elimination of the permanent chassis requirement (both regulatory and statutory), that change – even if it is ultimately achieved – is not, in and of itself, likely to pull the industry out of the production stagnation that has characterized the past two decades and catapult production levels to where they should be in an economy with a multi-million-unit affordable housing shortage. While such a change could benefit (primarily) the industry’s largest conglomerates, it would likely not be enough to more than double current industry production and, more importantly, would not be enough to super-charge industry production into the multi-hundreds of thousands of homes per year level, where it could and should be.

No, to do that, will require major changes in policy on a nationwide basis, and that is exactly what would flow from the elimination (or significant restriction) of discriminatory and exclusionary zoning combined with federal DTS support for manufactured home consumer lending within the affordable, mainstream chattel financing sector. The prohibition of exclusionary zoning under the enhanced federal preemption of the 2000 Reform Law would open-up to the industry and to manufactured housing consumers, large areas of the country where mainstream, affordable HUD Code homes are now either effectively or de jure banned (or severely restricted), while DTS support for the industry’s dominant chattel financing sector would draw more lenders into the market, resulting in lower, more competitive interest rates that would make mainstream HUD Code homes even more affordable for even larger numbers of Americans. The elimination of these bottlenecks on a national level would tremendously strengthen the ability of Americans in all areas of the country to access affordable mainstream manufactured homes and thereby super-charge demand for those same homes on a sustained basis.

Put differently, the elimination of these bottlenecks (as well as removing the shadow of harsh, unnecessary and discriminatory “energy” regulation on HUD Code homes), would fundamentally alter and improve the supply/demand profile of mainstream, non-subsidized HUD Code homes by enabling millions more potential purchasers to enter the HUD Code market than currently exist. By contrast, optional chassis flexibility, while expanding the marketability of certain manufactured homes in areas where they are already welcomed, would not generically and organically expand (to a significant degree) the mainstream manufactured housing market beyond its current-day parameters. It might benefit the profit margins and burnish the financial reports of the industry’s largest conglomerates, but it is not likely to significantly expand the HUD Code market per se.

To do that will require a tough fight to remove the industry’s main bottlenecks. The time is right. MHARR has already aggressively pursued these matters. But whether the broader industry and MHI are willing is another matter. Meanwhile, the clock is running on the second Trump Administration and the best opportunity that the industry is likely to have to remove the primary bottlenecks that have stunted its growth while harming Americans in need of affordable homeownership. The industry’s focus needs to be on winning the future, not just scoring overdue participation points.

Mark Weiss

MHARR is a Washington, D.C.-based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

“MHARR-Issues and Perspectives” is available for re-publication in full (i.e., without alteration or substantive modification) without further permission and with proper attribution to MHARR.