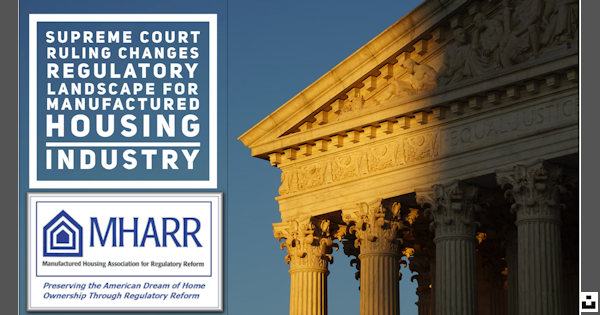

Supreme Court Ruling Changes Regulatory Landscape for Manufactured Housing Industry

The United States Supreme Court, on June 28, 2024, issued a landmark decision (anticipated by MHARR – see, MHARR’s May 2, 2023 memorandum, “Supreme Court Case Could Significantly Advance MH Producers’ Interests in Nation’s Capital,” copy attached) which will have significant long-term impacts on every federally regulated industry in the United States, including the comprehensively-regulated HUD Code manufactured housing industry.

The decision, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, eliminates a doctrine of federal regulatory law which has been in existence since 1984, known as “Chevron deference.” The Chevron doctrine, first enunciated by the Court in Chevron USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council, held that in litigation involving the interpretation of an allegedly ambiguous federal statute (or portion thereof), the interpretation given that statute by the federal agency charged with its enforcement would be given deference by a reviewing court. Thus, for example, in a hypothetical challenge involving the interpretation of any aspect of the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974, as amended by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law), the interpretation of the statute offered by HUD would be given deference by a reviewing court. This created major difficulties for manufactured housing producers in the 1980s and 1990s (continuing until today) and was a significant impetus for MHARR to pursue comprehensive reform of the original manufactured housing regulatory law in 2000.

Essentially then, under the Chevron doctrine, in virtually any case challenging HUD’s interpretation or application of the industry’s federal regulatory law – or the Department of Energy’s (DOE) ongoing interpretation of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2008 (EISA) and its horrific manufactured housing energy standards mandate – the “thumb would be on the scale” regarding that agency’s favored statutory interpretation in any conceivable court challenge. Because of that deference to agency rulemaking under Chevron, the industry would, in literally any regulatory court challenge since 1984, face a less-than 50-50 chance of success at the outset.

The elimination of the Chevron doctrine, however, in conjunction with the industry’s existing beneficial laws (i.e., the 2000 Reform Law and the duty to serve underserved markets) will now level the playing field in any court challenge to federal regulatory action involving an arguably ambiguous statutory provision. This sea-change in the calculus underlying regulatory challenges will inevitably impact virtually every decision made by federal regulatory agencies faced with the prospect of judicial challenges made more effective and impactful by the demise of the one-sided Chevron doctrine. As MHARR stated in its above-referenced May 2, 2023 memorandum, “if Chevron deference were overruled … the likelihood of judicial relief concerning many regulatory issues affecting the industry would be enhanced, meaning that agencies would have to confront an increased likelihood of credible litigation over regulatory decisions and actions. This, in turn, would enable MHARR to more aggressively protect, defend and advance the views and interests of manufactured housing producers in Washington, D.C.”

Put simply, the elimination of Chevron deference is an extremely positive development for every federally regulated industry, including the comprehensively-regulated HUD Code manufactured housing industry. Accordingly, the full implications of the Supreme Court’s Chevron ruling, specifically with respect to the HUD Code industry, will be more fully explored, examined and analyzed soon in an upcoming instalment of MHARR Issues and Perspectives.

As is reflected by MHARR’s founding motto – “Preserving the American Dream of Home Ownership through Regulatory Reform” – the industry pioneers and visionaries who established the MHARR-predecessor Association for Regulatory Reform were well-aware that unchecked regulation would be highly detrimental to a comprehensively-regulated industry and to the affordability and availability of manufactured homes. The Supreme Court’s Chevron deference ruling, fortunately, will help restore some of the balance between regulators and regulated parties that was lost during the Chevron era. And, with three regulation-driven bottlenecks suppressing the industry’s growth and evolution as recently detailed by MHARR, this fundamental change in the law could help the industry to chart a new course toward increased production and sales to meet the nation’s great and growing need for affordable homeownership.

The United States Supreme Court, on June 28, 2024, issued a landmark decision (anticipated by MHARR – see, MHARR’s May 2, 2023 memorandum, “Supreme Court Case Could Significantly Advance MH Producers’ Interests in Nation’s Capital,” copy attached) which will have significant long-term impacts on every federally regulated industry in the United States, including the comprehensively-regulated HUD Code manufactured housing industry.

The decision, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, eliminates a doctrine of federal regulatory law which has been in existence since 1984, known as “Chevron deference.” The Chevron doctrine, first enunciated by the Court in Chevron USA v. Natural Resources Defense Council, held that in litigation involving the interpretation of an allegedly ambiguous federal statute (or portion thereof), the interpretation given that statute by the federal agency charged with its enforcement would be given deference by a reviewing court. Thus, for example, in a hypothetical challenge involving the interpretation of any aspect of the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974, as amended by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law), the interpretation of the statute offered by HUD would be given deference by a reviewing court. This created major difficulties for manufactured housing producers in the 1980s and 1990s (continuing until today) and was a significant impetus for MHARR to pursue comprehensive reform of the original manufactured housing regulatory law in 2000.

Essentially then, under the Chevron doctrine, in virtually any case challenging HUD’s interpretation or application of the industry’s federal regulatory law – or the Department of Energy’s (DOE) ongoing interpretation of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2008 (EISA) and its horrific manufactured housing energy standards mandate – the “thumb would be on the scale” regarding that agency’s favored statutory interpretation in any conceivable court challenge. Because of that deference to agency rulemaking under Chevron, the industry would, in literally any regulatory court challenge since 1984, face a less-than 50-50 chance of success at the outset.

The elimination of the Chevron doctrine, however, in conjunction with the industry’s existing beneficial laws (i.e., the 2000 Reform Law and the duty to serve underserved markets) will now level the playing field in any court challenge to federal regulatory action involving an arguably ambiguous statutory provision. This sea-change in the calculus underlying regulatory challenges will inevitably impact virtually every decision made by federal regulatory agencies faced with the prospect of judicial challenges made more effective and impactful by the demise of the one-sided Chevron doctrine. As MHARR stated in its above-referenced May 2, 2023 memorandum, “if Chevron deference were overruled … the likelihood of judicial relief concerning many regulatory issues affecting the industry would be enhanced, meaning that agencies would have to confront an increased likelihood of credible litigation over regulatory decisions and actions. This, in turn, would enable MHARR to more aggressively protect, defend and advance the views and interests of manufactured housing producers in Washington, D.C.”

Put simply, the elimination of Chevron deference is an extremely positive development for every federally regulated industry, including the comprehensively-regulated HUD Code manufactured housing industry. Accordingly, the full implications of the Supreme Court’s Chevron ruling, specifically with respect to the HUD Code industry, will be more fully explored, examined and analyzed soon in an upcoming instalment of MHARR Issues and Perspectives.

As is reflected by MHARR’s founding motto – “Preserving the American Dream of Home Ownership through Regulatory Reform” – the industry pioneers and visionaries who established the MHARR-predecessor Association for Regulatory Reform were well-aware that unchecked regulation would be highly detrimental to a comprehensively-regulated industry and to the affordability and availability of manufactured homes. The Supreme Court’s Chevron deference ruling, fortunately, will help restore some of the balance between regulators and regulated parties that was lost during the Chevron era. And, with three regulation-driven bottlenecks suppressing the industry’s growth and evolution as recently detailed by MHARR, this fundamental change in the law could help the industry to chart a new course toward increased production and sales to meet the nation’s great and growing need for affordable homeownership.