Washington, D.C. 8.14.2025.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: MHARR

(202) 783-4087

MHARR PUBLISHES CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF

U.S. SENATE ROAD TO HOUSING ACT OF 2025

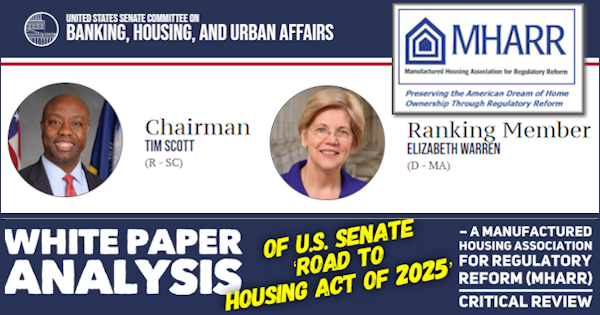

Washington, D.C., August 14, 2025 – The Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform (MHARR) has just released its White Paper analysis of the Senate ROAD to Housing Act of 2025 (see copy attached) that the Association had promised to develop and publish following the approval of that legislation by the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs on July 29, 2025.

While fully supporting adoption of the legislation’s provision effectively making a “permanent chassis” optional for new HUD Code manufactured homes, MHARR’s section-by-section methodical analysis outlines other manufactured housing-related provisions of the Bill that could harm the HUD Code industry and American consumers of non-subsidized affordable housing, while boosting its competitors.

The main thrust of MHARR’s analysis and critique is that the proposed legislation does not resolve – or even address in any form – the two principal post-production bottlenecks that have suppressed the growth and expansion of the industry and have prevented affordable, mainstream manufactured housing from reaching and fulfilling its full and complete potential within the housing market. These twin bottlenecks, as MHARR has analyzed and documented previously, are discriminatory and exclusionary state and/or local edicts that either bar or substantially restrict the placement of manufactured homes in many areas, and the lack of fully competitive interest rates – due to lack of federal securitization and secondary market support under the statutory Duty to Serve (DTS) mandate from mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – for consumer finance loans within the manufactured housing industry’s dominant personal property financing sector.

The MHARR analysis, accordingly, includes positive suggested amendments to cure these omissions, while offering suggested modifications to address other concerns with enumerated manufactured housing-related sections of the ROAD Bill, for consideration either by the full Senate or by the House of Representatives going forward.

In Washington, D.C., MHARR President and CEO, Mark Weiss, stated: “While MHARR welcomes the removal of the statutory ‘permanent chassis’ mandate for new manufactured homes, we are disappointed that our colleagues at the Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) – ostensibly the ‘lead’ industry organization advancing the manufactured housing-related aspects of this legislation – apparently allowed crucial deficiencies to be incorporated within the legislation while simultaneously omitting the most serious bottlenecks that have thwarted the industry.” Weiss continued, “Hopefully MHI will step forward and seek remedies to these issues as the legislative process unfolds.”

The Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform is a Washington, D.C.- based national trade association representing the views and interests of independent producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing.

— 30 —

Manufactured Housing Association for Regulatory Reform (MHARR)

1331 Pennsylvania Ave N.W., Suite 512

Washington D.C. 20004

Phone: 202/783-4087

Fax: 202/783-4075

Email: MHARRDG@AOL.COM

Website: www.manufacturedhousingassociation.org

— Text of MHARR White Paper —

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE

ROAD TO HOUSING ACT OF 2025

RESEARCHED AND PREPARED BY THE

MANUFACTURED HOUSING ASSOCIATION FOR REGULATORY REFORM

AUGUST 2025

A MHARR WHITE PAPER

I. INTRODUCTION

On July 29, 2025, the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs approved a bill initially proposed by its Chairman, Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC), entitled the “Renewing Opportunity in the American Dream to Housing Act” or “ROAD to Housing Act” (ROAD Bill). That legislation, which presumably will now go to the U.S. House of Representatives for further consideration, includes a number of provisions that will either directly or indirectly impact the availability and marketability of federally-regulated manufactured homes. Given the scope of this bill and its potential implications for both the manufactured housing industry and American consumers of affordable housing, it is essential that all of its various aspects be fully analyzed and, just as importantly, fully understood by all those with an interest in manufactured housing and, most particularly, by the smaller industry businesses that will be most profoundly impacted by those changes, if and once they are adopted.

Accordingly, the analysis that follows: (1) identifies provisions of the ROAD to Housing Act that can or will impact both the manufactured housing industry and consumers; (2) details the nature and likely extent of that impact; (3) offers potential corrections in certain cases; (4) identifies key manufactured housing issues that are not addressed by the ROAD Bill (but should be); and (5) offers suggested provisions that could (and should) be added to the bill to address those crucial deficiencies.

It must be stressed at the outset of this analysis, that MHARR does not object to – and, in fact, supports – a key component of the ROAD Bill, i.e., the Bill’s provision for optional chassis on HUD Code manufactured homes. MHARR, however, continues to maintain that any such modification must be carefully targeted so that it is not altered or subverted by possible amendments or modifications sought by other interests including, but not limited to, competitors within the broader housing industry, special interests, or HUD Code manufactured housing industry opponents.

Notwithstanding this support, however, the ROAD Bill, in its present form, is seriously deficient in that it fails to address, or even attempt to remedy, the two key policy bottlenecks that have functioned to suppress the supply and utilization of HUD Code manufactured homes, particularly over the last decade. For the ROAD Bill to have any substantial impact, therefore – that will reach the ground to deliver actual benefits for manufactured housing consumers and the industry as a whole – there are additions/amendments to the Committee-passed version of the ROAD Bill that should be included when (and if) the ROAD Bill is considered in the full Senate and the House of Representatives.

II. INDUSTRY BOTTLENECKS

In analyses prepared and sent to senior officials at both HUD and the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) in May 2024, MHARR identified – and called for action to address and resolve – “the two principal bottlenecks that continue to suppress the production, marketing and availability of affordable, mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing in the midst of an unprecedented affordable housing crisis.”[1]

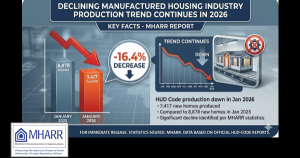

MHARR, initially observed that “at a time when housing affordability in the United States has reached an all-time low according to press reports, the production of inherently affordable, mainstream manufactured housing, costing, on average, less than 25% of the price of an average site-built home, according to the most recent available annual U.S. Census Bureau data, fell more than 21% in 2023, to 89,169 homes. This marks the 15th year since 2007, that annual manufactured housing industry production has fallen below the crucial 100,000 home benchmark – a benchmark that was routinely and regularly exceeded in earlier years and decades.”

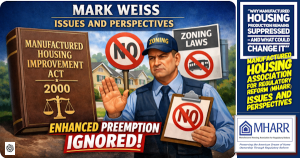

Based on this MHARR stated, “while there are multiple factors having a negative impact on the affordable, mainstream manufactured housing market, there are two in particular that, over the long-term, have prevented the industry from reaching its full potential as the nation’s premiere source of affordable, non-subsidized homeownership. These post-production bottlenecks … are: (1) the failure of FHFA and the FHFA-regulated Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) (i.e., Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), to provide any type of securitization or secondary market support for the dominant personal property consumer financing sector of the manufactured housing market under the statutory Duty to Serve Underserved Markets (DTS) mandate; and (2) HUD’s failure to utilize the enhanced federal preemption of the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law) (i.e., existing law) to invalidate – or even challenge – discriminatory and exclusionary zoning laws targeting manufactured housing and manufactured housing residents.

Because of the persistent failure of federal government agencies and related federal officials to comply with these clear and unambiguous statutory mandates, affordable manufactured homes are effectively banned (with no consequence) from many areas of the United States where the need for affordable homeownership is greatest. At the same time, millions of potential manufactured homebuyers are forced to seek purchase money loans at unnecessarily high and arguably excessive interest rates due to the discriminatory absence of federal securitization and secondary market support within the dominant manufactured housing personal property consumer financing sector. These unnecessarily high rates can – and do – exclude many lower and even moderate-income Americans from the mainstream manufactured housing market and, as a consequence, from homeownership altogether. Both such failures – in violation of applicable law — have inevitably undermined the affordable housing role of mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing and are unacceptable.

Both of these bottlenecks, however, can (and, indeed, must) be resolved via additions and amendments to the ROAD Bill that can be inserted during the upcoming legislative process. Meanwhile, the various deficiencies that already exist in the Senate bill, as detailed below, can also be rectified as part of the ongoing legislative process.

Accordingly, set out below is a section-by-section analysis of the ROAD Bill which highlights areas of concern and key omitted issues. Thereafter, MHARR sets forth language for additions/amendments to the Senate and/or House version of the ROAD Bill that would cure those deficiencies if included.

III, ANALYSIS OF PENDING LEGISLATION

A. ROAD Bill Section 203: Section 203 of the ROAD Bill encompasses the previously free-standing Housing Supply Frameworks Act of 2025 (HSFA). MHARR has previously analyzed and suggested modifications to this legislation as follows –

- Subsection (b) “Definitions”: At page 13, after line 25 between subsections (3) and (4), add the following new subsection (4): “The term ‘manufactured home’ or ‘manufactured housing’ as used herein, has the same meaning and definition as the term ‘manufactured home’ as defined in 42 U.S.C. 5402(6)” and redesignate current subsections (4) and (5) accordingly.

MHARR Analysis: The term “manufactured home” (and/or the plural thereof, “manufactured housing”) should be defined so as to clearly specify the types of homes embraced by the Bill. The proposed definition refers back to the definition of “manufactured home” already set forth by federal law in the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 as amended by the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (mandating and providing for federal manufactured housing regulation, utilizing uniform, performance-based federal standards, uniform enforcement and robust federal preemption) and is incorporated without modification in state law and local ordinances around the nation. This reference definition would specifically further provide that it includes and incorporates any changes to the statutory definition of “manufactured home” made by or within the ROAD Bill itself, such as the statutory deletion of the “permanent chassis” mandate.

- Subsection (c)(2)(B): At page 15, after line 13, between current subsection (ii) and (iii), add a new subsection (iii): “Producers of federally-regulated manufactured housing” and redesignate all following subsections accordingly

MHARR Analysis: The current Bill language limits participation to “manufactured housing developers.” This formulation is more attuned to the site-built housing industry than to the mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing industry. The membership categories, accordingly, should be broadened to include specific participation by “manufactured housing producers.” Within the business model of the manufactured housing industry (unlike the site-building industry), home producers (i.e., home builders) are not synonymous with community “developers” and have interests that are in many respects separate and distinct from “developers.” In order to represent a valid and legitimate cross-section of interests (and to ensure participation by those most directly impacted by state and local zoning restrictions as well as the federal regulatory system with its performance-based federal standards, uniform enforcement and federal preemption), “manufactured housing producers” should be specifically identified and provided representation on the task force described by the Bill.

- Subsection (c)(3)(B): At page 16, after line 16, between current subsection (iii) and subsection (iv), add a new subsection (iv): “The elimination of discriminatory zoning, placement, and other restrictions against federally-regulated manufactured homes, including but not limited to the federal preemption of such restrictions pursuant to section 42 U.S.C. 5403(d) of the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 (1974 Act), as amended” and redesignate all following subsections accordingly.

MHARR Analysis: This addition is needed because manufactured homes, as a specific class of affordable housing (and manufactured homeowners, as a specific class of homebuyer) face targeted, discriminatory and, in frequent cases, exclusionary zoning-based restrictions against home placement because of their construction in accordance with a federal building code (or other “fig-leaf” claims or theories). Therefore, the Bill should specifically target the elimination of such restrictions as a fundamental element of its mission and purpose and should reiterate and validate the authority of HUD, under existing federal law, to federally preempt any such restrictions. The proposed language would target such baseless restrictions and elevate the importance of their elimination as a key feature of the Bill. (See also, Section [ ], below regarding an appropriate and necessary amendment to reinforce HUD’s preemptive authority over zoning exclusion of manufactured homes).

- Subsection (c)(3)(b): At page 17, line 8, under subsection (vii), after “the reduction of obstacles to” insert “the availability and utilization of federally-regulated manufactured housing and delete the remainder of that subsection. After revised subsection (vii) add a new subsection (viii) stating: “the reduction of obstacles to a range of other housing types at all levels of affordability including modular housing” and redesignate all following subsections accordingly.

MHARR Analysis: The current Bill language groups manufactured homes together with “modular housing.” This is unworkable and unacceptable, and will result in unintended negative consequences, particularly in light of other provisions contained within the Bill (see, e.g. Section 302 analysis, below). Although manufactured and modular homes are both constructed in factories and thus offer greater “affordability” than site-built homes, they are entirely different species of construction, built to differing and incompatible building codes. Manufactured homes are constructed in a factory in accordance with a performance-based federal building code. The uniform standards of that code, together with uniform federally-based enforcement and robust federal preemption, ensure the unparallelled affordability of mainstream HUD Code manufactured homes. By contrast, “modular homes” are built in accordance with the International Residential Code (IRC) (or variations thereof) adopted under state or local law. These state/local codes do not have a specific mandate for affordability and result in homes (both site-built and modular) with a significantly higher cost profile than manufactured homes built in accordance with the HUD Code. Consequently, the Bill should not conflate these significantly different types of homes within an overly-broad statement as is contained in the current version of the Bill. MHARR’s suggested correction would separate the two types of construction so that each can be treated and considered as a unique and distinct entity.

- Subsection (c)(3)(C)(iv): At page 20, line 16-17, replace the word “attainable” with the word “affordable.”

MHARR Analysis: The term “attainable” has no fixed or specific pre-existing meaning within a housing context and should be avoided specifically in relation to manufactured homes. Instead, that term should be replaced by the term “affordable” which: (1) is consistently used in housing legislation; (2) is specifically referenced as a purpose and objective of federal manufactured housing law under the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 and; (3) is, in fact, defined in this very section of the ROAD Bill (i.e., Section 203(b)(1)). While the ROAD Bill, in certain provisions unrelated to manufactured housing does attempt to define attainability, that concept is alien to federal manufactured housing law and policy pertaining to “affordable” federally-regulated manufactured housing, and would cause confusion and potential chaos regarding pre-existing statutory mandate regarding the mandatory affordability of manufactured housing and the mandatory cost-benefit consideration of regulations specifically impacting HUD Code manufactured housing.

For the same reason, the term “attainable” should be avoided or deleted in any legislation regarding optional chassis for manufactured homes in the House of Representatives. Specifically, draft legislation to permit optional chassis for manufactured homes, entitled the “Expansion of Attainable Homeownership Through Manufactured Housing Act of 2025,” was offered in May 2025 by Rep. John Rose (R-TN). (Emphasis added). Again, the term “attainable” should be deleted and replaced with the term “affordable.”

Pre-existing federal law, most particularly the 1974 Act, as amended, already refers specifically to federally-regulated manufactured housing as “affordable” housing and, just as importantly, makes it clear exactly what “affordability” means (i.e., the initial acquisition price of the home) and who the beneficiary of that “affordability” must be (i.e., the initial homebuyer). See, e.g., section 5401(b) of the 1974 Act, as amended, which states that the purposes of the Act are, among other things, to:

- (1) “Protect the quality, durability, safety and affordability of manufactured homes;”

- (2) “Facilitate the availability of affordable manufactured homes;” and …

- (8) “Ensure that the public interest in , and need for, affordable manufactured housing is duly considered in all determinations relating to the federal standards and their enforcement.”

(Emphasis added). Moreover, the concept of acquisition price affordability for the home purchaser is prominently enshrined in section 5403(e)(4) of the 1974 Act, as amended, which provides that the Manufactured Housing Consensus Committee (MHCC) in recommending manufactured housing standards, regulations and related interpretations, and the HUD Secretary, in adopting standards, regulations and interpretations, “shall consider the probable effect” of such action “on the cost of the manufactured home to the public.” (42 U.S.C. 5403(e)(4)).

To now associate the subjective, fundamentally meaningless and undefined term “attainable” with manufactured housing would create an unnecessary conflict between that term and the term and concept of “affordability,” and potentially place an unintended legislative gloss on the term “affordability,” (used in the 1974 Act as amended and in other federal and state statutes) which could undermine that concept and create an unnecessary and destructive avenue for the imposition of extreme and non-cost-effective standards on the manufactured housing industry and consumers.

Further, and just as indefensible, is the fact that the term “attainable” has been specifically and extensively used for marketing purposes by the industry’s largest manufacturer, Berkshire-Hathaway subsidiary Clayton Homes, Inc. (Clayton). For that same marketing term to now be inserted in federal legislation, would bestow an unwarranted and baseless imprimatur — and implicit federal endorsement — of Clayton proprietary products that would discriminate against and be harmful to the legitimate market interests of other industry manufacturers and – most particularly — smaller manufacturers. Accordingly, the term “attainable” must be avoided in a manufactured housing context.

B. ROAD Bill Section 301: Section 301 of the ROAD Bill addresses the definition of “manufactured home” and also includes language regarding federal preemption. The following specific sections and issues urgently need to be addressed —

- Subsection (a): Subsection (a) of Section 301 of the ROAD Bill would strike the language “on a permanent chassis” contained in 42 U.S.C. 5402(6) of the 1974 Act, as amended, and replace that clause with new language stating: “with or without a permanent chassis.” As it has since its establishment in 1985, MHARR supports this amendment, without modification, change or alteration. Based on its long-term experience, however, MHARR has consistently warned that the open legislative process, if not managed carefully and in a highly targeted and disciplined manner, could result in further or later alterations that would be inconsistent with the best interests of HUD Code producers. As a result, MHARR has urged caution in pursuing such a change which has essentially lain dormant for forty years, until now, when the industry’s largest manufacturers are apparently seeking such a change to augment their competitive position in relation to other smaller producers.

MHARR Analysis: In the 1980s, shortly after MHARR was established, there was an effort in Congress, led by MHARR, to delete the “permanent chassis” requirement that had been incorporated into the original 1974 law. Such a provision, contained in the so-called “Hiler Amendment” (named for its principal House of Representatives sponsor, Rep. John Hiler) was ultimately included in the House version of the 1990 housing bill. The Manufactured Housing Institute (MHI) initially supported that amendment, but later withdrew its support just prior to consideration of the amendment by a House-Senate conference committee. Thus, the Hiler amendment failed, and the chassis issue has persisted.

Now, with some of its largest corporate conglomerate members seemingly intent on blurring the lines between types of homes and different types of production, and seemingly fixated on creating markets for higher-priced manufactured housing (like so-called “cross-mod” homes), as contrasted with affordable, mainstream HUD Code homes, MHI is seeking to eliminate the requirement for a “permanent chassis.”

At the policy level, though, while MHARR has continued to support the elimination of the permanent chassis requirement (both regulatory and statutory), that change – even if it is ultimately achieved – is not, in and of itself, likely to pull the industry out of the production stagnation that has characterized the past two decades and instead catapult production levels to where they should be in an economy with a multi-million-unit affordable housing shortage. While such a change could benefit (primarily) the industry’s largest conglomerates, it would likely not be enough to send industry production into the multi-hundreds of thousands of homes per year level, where it could and should be.

To do that will require the elimination (or significant restriction) of discriminatory and exclusionary zoning combined with federal support for manufactured home consumer lending within the affordable, mainstream chattel financing sector. The prohibition of exclusionary zoning under the enhanced federal preemption of the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000 (2000 Reform Law) would open-up to the industry and to manufactured housing consumers, large areas of the country where mainstream, affordable HUD Code homes are now either effectively or de jure banned (or severely restricted), while support under the “duty to Serve” (DTS) mandate for the industry’s dominant chattel financing sector would draw more lenders into the market, resulting in lower, more competitive interest rates that would make mainstream HUD Code homes even more affordable for even larger numbers of Americans. The elimination of these bottlenecks on a national level would tremendously strengthen the ability of Americans in all areas of the country to access affordable mainstream manufactured homes and thereby super-charge demand for those same homes on a sustained basis.

Put differently, the elimination of these bottlenecks (as well as removing the shadow of harsh, unnecessary and discriminatory “energy” regulation on HUD Code homes), would fundamentally alter and improve the supply/demand profile of mainstream, non-subsidized HUD Code homes by enabling millions more potential purchasers to enter the HUD Code market than currently exist. By contrast, optional chassis flexibility, while expanding the marketability of certain manufactured homes in areas where they are already welcomed, would not generically and organically expand (to a significant degree) the mainstream manufactured housing market beyond its current-day parameters. It might benefit the profit margins and burnish the financial reports of the industry’s largest conglomerates, but it is not likely to significantly expand the HUD Code market per se.

For further discussion of the principal industry bottlenecks and the need for their remediation in this Bill, see the “Omitted Issues” section below.

- Subsection (e): Subsection (e) of the ROAD Bill, at present, is a savings clause apparently designed to preserve federal preemption under the 1974 Act as amended. This formulation, however, misses a profound opportunity to address and substantively correct one of the principal national bottlenecks that has needlessly suppressed the utilization of inherently affordable manufactured housing in communities around the United States – e., discriminatory zoning exclusion (and undue restriction).

MHARR Analysis: Rather than simply restate the continuing applicability of existing law, this section should be amended to further clarify that federal preemption does, in fact, apply to the zoning exclusion of manufactured housing and that HUD has a statutory obligation under the pre-existing preemption provision of the 2000 Reform Law to take action to prevent or eliminate exclusionary zoning mandates. Specific suggested language for such an amendment is included in the section entitled “Suggested Additions/Amendments to Pending Legislation,” below.

C. ROAD Bill Section 302: ROAD Bill section 302 is entitled the “Modular Housing Production Act.” This section has multiple objectionable provisions —

- Subsection (b): This section specifically calls for studies and actions to identify, evaluate and address “regulatory and programmatic features that restrict participation in construction financing programs by modular housing developers.”

MHARR Analysis: Exactly why this section, pertaining specifically to modular housing, was included in Title III of the ROAD Bill, entitled “Manufactured Housing for America” (emphasis added), is unclear. What is clear, however, is that the conflation of modular and manufactured housing, at the heart of this section, will lead to significant public and governmental confusion over the production, regulation and acquisition of these fundamentally different types of homes, which will only be exacerbated by the preceding elimination of the permanent chassis mandate for manufactured homes under section 301 of the ROAD Bill. Accordingly, this portion of section 302 should either be deleted or moved to a completely different title of the ROAD Bill.

- Subsection (c): Also unclear is the intent and specific meaning of subsection (c) of this provision, which directs the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to “award a grant to study the design and feasibility of a standard uniform commercial code for modular homes,” which would include “streamlining design and construction” of such homes, and “a means to coordinate a standardized code with financing incentives.” (Emphasis added).

D. MHARR Analysis: From the language used, this section reads suspiciously like a mandate to explore the possibility of a uniform federal construction code for modular homes, like the code and related enforcement mechanisms that currently exist for federally-regulated manufactured homes, enforced by HUD. As such, this language, at a minimum, will further drive negative impacts related to the conflation of manufactured and modular homes at various levels of government, and could ultimately undermine the competitive and affordability advantage currently held within the housing market by manufactured homes, by providing a basis for the regulation of modular home construction and safety based on a structure similar – if not identical to – that which currently exists for manufactured housing.

- ROAD Bill Section 303: ROAD Bill section 303 addresses home financing and other seemingly unrelated matters as follows —

Subsection (a)(1)(B): This subsection would modify the limits under the National Housing Act for loans relating to the alteration, repair, improvement or purchase of manufactured homes and would mandate the development of a method for indexing such limits on an annual basis.

MHARR Analysis: MHARR has no objection to the revised limits specified in the bill and has no objection to the annual indexing of such limits.

- Subsection (b): This subsection would mandate a HUD study of “off-site construction housing,” specifically including both “manufactured homes and modular homes.”

MHARR Analysis: MHARR strenuously objects to this mandate. First, MHARR objects to the insertion, in a federal statute, of the undefined and non-specific term “off-site construction housing.” This term has not been previously utilized in federal legislation pertaining to federally-regulated manufactured homes and would further exacerbate the conflation of manufactured and modular homes at all levels of government. Second, a unitary study of federally-regulated manufactured housing and non-federally-regulated modular housing would further add to and exacerbate the conflation of manufactured and modular homes at all levels of government and would further cause confusion for consumers and potentially subject consumers to unethical sales and business practices. For these reasons, this entire section should be deleted from any final bill.

E. ROAD Bill Section 304: Section 304 of the ROAD Bill provides for grants to certain manufactured housing communities. MHARR has no objection to these amendments.

F. ROAD Bill Section 401: Section 401 of the Road Bill contains provisions requiring studies and reports by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) regarding “small dollar mortgages,” defined as mortgages with a principal obligation not exceeding $100,000 on homes titled as real property. The mandated study and report would specifically be required to address points and fees in connection with such loans. While this provision appears to be specifically targeted to protect and benefit Clayton Homes, Inc. financial subsidiaries 21st Mortgage and Vanderbilt Mortgage Corp., it could nonetheless have certain positive impacts if amended.

MHARR Analysis: Subsection 401(a) limits the definition of “small dollar mortgages” to mortgages “secured by real property.” This should be amended to state “secured by real or personal property.” Such a modification would expand the provision to cover and include manufactured home personal property loans, which comprise nearly 80% of the entire HUD Code manufactured housing consumer financing market and provide the most affordable source of homeownership for lower and moderate-income Americans.

IV. OMITTED ISSUES

While the ROAD to Housing Bill would address and correct a long-standing issue under the HUD Code, i.e., the requirement for a “permanent chassis” which restricts – or renders more costly — the design options available to manufactured housing consumers, and would simultaneously elevate consideration of certain issues pertaining to the zoning-based exclusion or substantial restrictions on the utilization and placement of HUD Code manufactured homes, it would not definitively remedy the two principal bottlenecks that over the long term have – and continue to – suppress the availability and utilization of inherently affordable, mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing. These two principal bottlenecks, as previously detailed by MHARR, are: (1) discriminatory zoning exclusion; and (2) lack of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac support for manufactured home consumer personal property lending. The omission of definitive remedies for these two primary bottlenecks substantially undermines the value of the ROAD Bill for both manufactured housing consumers and the industry, and would leave in place the most significant obstacles to the greater utilization and availability of manufactured housing for Americans across the United States.

To fully understand this failure requires a knowledge of the industry’s history and evolution. The manufactured housing industry and manufactured homes have undergone a remarkable transformation process since their initial emergence during the Post-World War II era. From vehicle-like “travel trailers,” manufactured homes parted ways with recreational vehicles during that initial period and, with the enactment of the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act in 1974, acquired the legal status of “housing.” It was not until the adoption of the Manufactured Housing Improvement Act of 2000, however, that HUD Code manufactured homes assumed the full status of modern, legitimate housing for all purposes. In part, the 2000 Reform Law underscored and emphasized the last step in that nearly 80-year evolution from specialty vehicle to legitimate “housing,” by substantially strengthening the federal preemption clause of the 2000 Reform Law, to over-ride any and all state or local “requirements” – and not just construction or safety standards – that impair the federal superintendence of the industry. The 2000 reform law, accordingly, recognizes the ultimate status of HUD Code homes as legitimate “housing” for all purposes, while simultaneously strengthening federal preemption in order to ensure that the availability of that legitimate, inherently affordable housing, would not be impaired by discriminatory measures designed to (or having the effect of) excluding mainstream HUD Code homes.

Unfortunately, though, the enhanced preemption provided by Congress as part of the 2000 Reform Law, has not been used or enforced by HUD in order to begin the process of breaking down entrenched state and/or local resistance to the placement and utilization of HUD Code homes. As a result, the patterns of exclusion that have long existed in many areas of the United States, particularly including urban and suburban areas, still remain, with homeownership opportunities correspondingly limited for lower and moderate-income populations in those areas. In substantial part, it is these discriminatory exclusion mandates that have impaired the growth and expansion of the industry, and its ability to provide affordable, non-subsidized homeownership for substantial numbers of Americans as envisioned by Congress. To the contrary, annual production levels of HUD Code homes during the post-1974 Act era, have been broadly lower than those which predominated during the pre-federal regulation period, while annual production levels since 2009 have been extraordinarily lower than both 20-year and 30-year industry production averages. Consequently, during a period that has seen the average cost of a single-family site-built home balloon, while the availability of lower-cost affordable housing has declined and is millions of units below the existing need according to a 2021 report by Fannie Mae, the overall utilization and sales of inherently affordable HUD Code manufactured homes has incongruously declined.

Thus, at a time when the need for affordable, non-subsidized homeownership has never been greater, and the affordability of manufactured homes, vis-à-vis site-built homes (including both purchase price and home operation costs) has never been greater, the availability and utilization of HUD Code homes remains much closer to historic lows than the industry’s modern-era production high of 373,000 homes in 1998. Moreover, and even more importantly, industry production levels do not – and have not – even approached the levels, in the hundreds of thousands of homes, that the industry should be producing based on the documented need for millions of additional units of affordable homes.

This production and utilization shortfall in relation to inherent affordability is, in turn, a product of two principal factors, which continue unabated: (1) discriminatory state and local zoning and placement exclusions; and (2) discriminatory consumer financing limitations.

As MHARR has fully documented, discriminatory zoning and placement restrictions and/or exclusions prohibit modern, inherently affordable manufactured homes from many areas of the United States, including areas of concentrated poverty or housing poverty, where affordable homeownership is particularly needed. This includes, but is not limited to, many urban and suburban areas, where HUD-regulated manufactured housing could be a private-sector source of affordable homeownership, or a component of public-sector affordable housing initiatives, but has been – and continues to be — excluded either as a result of de jure zoning/placement exclusions or de facto reluctance and hesitancy related to zoning and placement restrictions. Thus, while manufactured housing is nominally included in any number of existing federal affordable housing programs, its actual deployment and utilization in many areas is effectively prohibited by such zoning and placement exclusions. Those exclusions, in turn, could be overridden by HUD pursuant to the enhanced federal preemption authority provided by the 2000 Reform Law, but HUD has consistently refused to yield that power in support of American consumers of affordable housing.

In addition to zoning and placement discrimination, the utilization of mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing has also been undermined by the unavailability of market-competitive consumer financing for such homes as a result of the failure and refusal of the federal mortgage giants, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, to provide support for manufactured housing personal property loans (comprising nearly 80% of the entire HUD Code market) pursuant to the statutory Duty to Serve Underserved Markets (DTS). The failure to fully and substantially implement DTS within the manufactured housing market for nearly two decades after the enactment of the DTS mandate, effectively forces manufactured homebuyers to pay unnecessarily high interest rates on

manufactured home purchase loans, to a small group of portfolio lenders which effectively dominate the HUD Code consumer financing market. This, in turn, excludes qualified but marginal borrowers who would qualify for financing in a market with legitimately competitive – and, therefore, lower, borrowing rates.

In combination, these fundamental deficiencies within the manufactured housing market, which impair the industry’s ability to compete with other types of homes on a level playing field – despite the inherent affordability of manufactured homes – has suppressed and repressed both the growth of the industry and its ability to serve a larger segment of Americans in need of affordable homeownership.

Consequently, in order for manufactured housing to play a significantly greater role in remedying the nation’s overwhelming – and growing – need for truly affordable homeownership, it is essential that these governmental failures be remedied. The following section contains suggested provisions that must be added to the pending Bill in order to address these issues.

V. SUGGESTED ADDITIONS/AMENDMENTS TO PENDING LEGISLATION

In order to address and ensure the remediation of state and/or local zoning restriction or exclusion of manufactured homes, section 301(e) at page 104, lines 11-16 should be amended as follows:

“PREEMPTION –Nothing in this section or the amendments made by this section shall be construed as limiting the scope of federal preemption under section 604(d) of the National Manufactured Housing Construction and Safety Standards Act of 1974 as amended (42 U.S.C. 5403(d). The Secretary shall fully implement federal preemption under that section to prevent, prohibit and/or remedy the zoning exclusion or discriminatory restrictions on the placement of manufactured homes in any state or local jurisdiction thereof.”

Furthermore, in order to make it absolutely clear that the Duty to Serve fully extends to and encompasses the personal property loans which comprise nearly 80% of the mainstream HUD Code manufactured housing market, new sections should be included in the ROAD Bill as follows:

“Amend section 12 U.S.C. 4565(a)(1)(A) as follows: ‘The enterprise shall develop loan products and flexible underwriting guidelines to facilitate a secondary market for mortgages on manufactured homes for very low-, low-, and moderate-income families. Such mortgages shall include loans secured by manufactured homes titled as real property and by manufactured homes titled as personal property.’”

“Amend 12 U.S.C. 4565(d)(3) as follows; ‘(3) Manufactured housing market — In determining whether an enterprise has complied with the duty under subparagraph (A) of subsection (a)(1), the Director shall consider loans secured by both real and personal property.’”

With these amendments included, the ROAD Bill would substantially address and remedy the bottlenecks that have needlessly suppressed the manufactured housing market while denying all of the benefits of homeownership to millions of lower and moderate-income Americans who have effectively been excluded from the housing market due to ballooning housing costs. These changes are necessary and essential for mainstream, affordable manufactured housing to help remedy the nation’s affordable housing crisis, while energizing the production of manufactured homes to new levels in the hundreds-of-thousands of homes per year.

VI. CONCLUSION

While MHARR supports the deletion of the statutory permanent chassis requirement for manufactured homes as provided by the ROAD Bill, that bill, in its present form, would leave unresolved and uncorrected two much more serious bottlenecks to the greater utilization of manufactured homes as a key source of affordable homeownership – i.e., discriminatory zoning exclusion and the absence of federal support for the vast bulk of manufactured home consumer lending represented by personal property loans. For the ROAD Bill to have a major remedial impact within the affordable housing market, this deficiency must be addressed and corrected. To achieve this, MHARR strongly urges Congress to augment the ROAD Bill with the additional suggested provisions set forth above. To do otherwise would waste a profound opportunity to ensure the greater availability of affordable homeownership for millions of Americans who might otherwise be unable to access the American Dream of homeownership.

—

[1] While baseless, excessive and needless “energy conservation” standards by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) also represent an illegitimate bottleneck suppressing the utilization of inherently affordable manufactured housing, energy standards are beyond the scope of the ROAD Bill and are, therefore, not addressed in this Paper.

—